Timing is everything. This exhibition, which addresses Surrealist art during the years when Europe fell to extreme Nationalism and tyrants— from Mussolini, to Franco, to Hitler—especially resonates for audiences today, who see parallels to an increase in Nationalist rhetoric around the world, including in the US. Indeed, when later looking back upon Surrealism, one of its founders and writer of several manifestos, André Breton, specifically viewed it through the lens of Nationalism and war.

Organized around four major historical events: the rise of Fascism, the Spanish Civil War, the beginning of WWII, and the flight of European Surrealists to the America’s, the exhibition, co-organized by curators at the Baltimore Museum of Art and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, also considers the various types of Surrealism prevalent at the time, from the figurative to the abstract. Despite different approaches, the Surrealists shared a distrust of authority and an interest in the field of psychology and the new recognition of the unconscious.

Building on the two important collections of Surrealist art at their respective institutions, the curators attempt to define monstrousness, to ask why monsters appeared at this time in the Surrealist imagination, and to determine if there were variations of the monstrous that might have been used for specific purposes.

The works on view are in superb condition, providing an opportunity to view both well-known and lesser known Surrealist paintings, prints, and sculptures, some of which are rarely on view and others from private collections.

Of the nearly 90 works in the exhibition, in addition to those by major artists like Picasso, Dali, Miro, and Masson, many are by key figures closely connected to Surrealism, such as Leonora Carrington, Arshile Gorky, Wilfredo Lam, Maria Martins, Roberto Matta, Isamu Noguchi, Kay Sage, Yves Tanguy, Dorthea Tanning, as well as by those who began their careers under the influence of Surrealism but are more closely associated today with Abstract Expressionism: William Baziotes, Robert Motherwell, Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and David Smith.

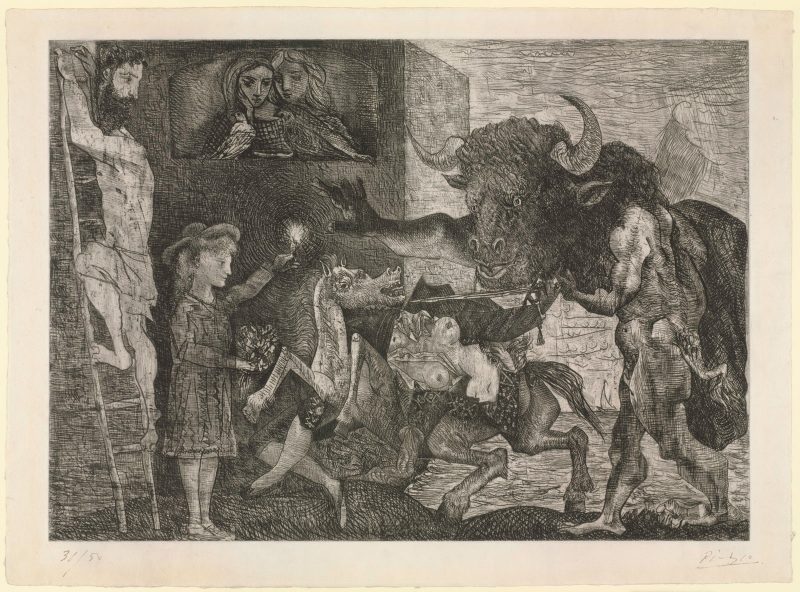

Picasso’s Minotauromachy, an etching, is in the section entitled Premonition of War. The man/bull creature represents the growing fascination by the Surrealists with the relationship between art and politics, seeing the animal’s symbolic association with the myth of the labyrinth and the irrationality of a monster in opposition to Europe’s descent into Fascism. This image also reflects conflicts in Picasso’s personal life as well as the Spanish bullfighting tradition. He contributed the first cover design for the Surrealist oriented magazine, Minotaur, 1933, a copy of which is included in the exhibition.

For the Surrealists, World War I and the growing Nationalism that followed it represented rational thought, thus their turn to the interior, the subjective, dreams, and nightmares. The monstrous increasingly appeared as a focus as the actuality of war became ever more real.

Masson’s intensely colored painting on a similar subject, Tauromachie, includes a ferocious bull and the mirrored figures of the matador, one below on the ground in agony and the other above, possibly dreaming of his death. Masson fought for France in WWI and was severely injured; later, living for several years in Spain (a result of his close friendship with Miro), he created many works on the topic of the bullfight. This painting, produced after his exit from Spain due to the civil war there, symbolizes violence, terror, and devastation and was likely influenced by Picasso’s Guernica. Masson lived for several years in Nazi occupied France, eventually escaping to the U.S. in 1941, along with his wife and two children. Political and social upheaval result in refugees.

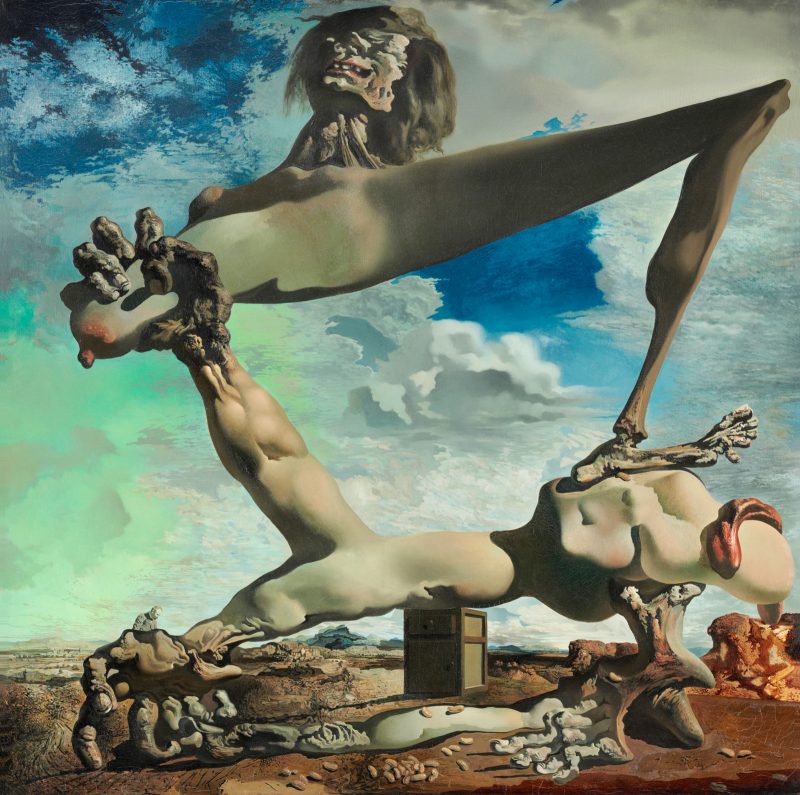

One of the most well-known images in the show is Dali’s Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of Civil War), familiar to visitors of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. It was followed a year later by his Invention of the Monsters, (Art Institute of Chicago). According to Curator Tostmann, as Fascism grew, images of monsters by the Surrealist artists multiplied. Dali, in writing to the AIC in 1943 commented, “According to Nostradamus the apparition of monsters presages the outbreak of war.”* The meticulously depicted twisted and tortured body is monstrous and a comment on the horrific civil war in Dali’s native Spain.

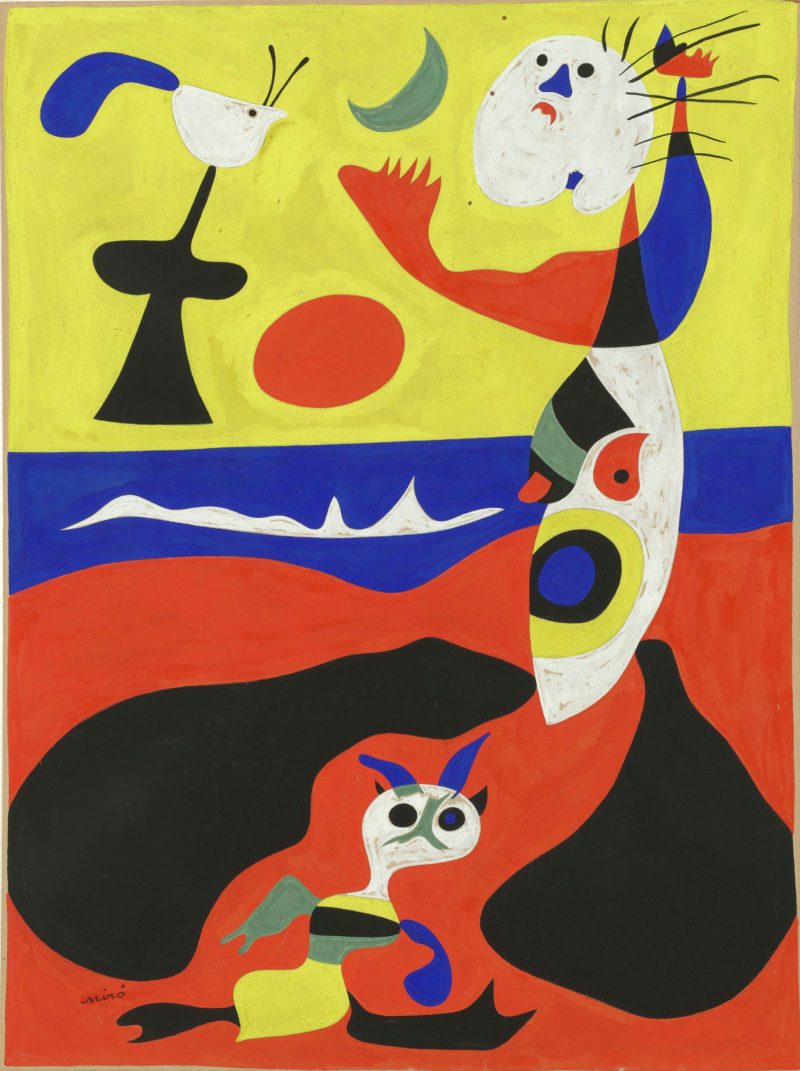

Miro, also a Spaniard, who had known Dali for years but was never an official member of the Surrealist group, preferred an abstract style of Surrealism based on devices like automatism and the unconscious. Several works by him are included and one from this period, Seated Personages, a small oil on copper painting, comprises attenuated forms that are part human and part bird. Seated Personages and another work, Summer, contain agitated and disturbed creatures and heightened colors. Their anxiety extends to viewers even today, or especially now; we too live in uneasy times and can empathize with these troubled beings.

Ernst painted Europe after the Rain II between 1940-42, shipping the unfinished canvas to the Museum of Modern Art, and completing it once he arrived in the U.S. As a German, he was an illegal foreigner in France, arrested and escaped the Nazis, and ultimately aided by Peggy Guggenheim, found refuge in the U.S. The painting’s friezelike horizontal format presents a world after a horrific meltdown, seemingly prescient of the later firebombing of Dresden and the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Ernst includes a few figures: a tiny nude Europe(a) rides a mechanical bull, a bird-like male figure faces an armless female, and some nymphs occupy the bottom left. His technique, Decalcomania, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Decalcomania results in smeared and fluid forms that reek of disquiet. Maria Martins’s sculpture, Sacred Ones, shares similar forms to that of Ernst. She showed her work in several Surrealist exhibitions.

Though the works in Monsters and Myths are elegantly installed in pristine galleries, the anxiety and concern expressed in them is palpable. This is an exhibition for our times, for an anxious world grappling with rising Nationalism and demagogic leaders, climate change, unending wars, and refugee crises. Artists may have different ways of addressing these issues today, but it is worth examining how they dealt with them in the past.

The comprehensive and illustrated catalog, which amplifies the discussion about these concerning issues contains four extensive essays, not only by the curators, Oliver Shell, BMA Associate Curator of European Art, and Oliver Tostmann, Susan Morse Hilles Curator of European Art at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, but also by important scholars of Surrealism: Samantha Kavky and Robin Adèle Greeley.

Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s is on view at the Baltimore Museum of Art from February 24, 2019 — May 26, 2019. Monsters & Myths is co-organized by The Baltimore Museum of Art and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art in Hartford, Connecticut.

*Salvador Dali telegram to the Art Institute of Chicago, cited in Oliver Tostmann, “The Surrealists and Their Monsters in A ‘Time of Distress,’” in Oliver Shell and Oliver Tostmann, eds,. Monsters & Myths: Surrealism and War in the 1930s and 1940s (New York City: Rizzoli Electra, 2018), 19.

More Photos