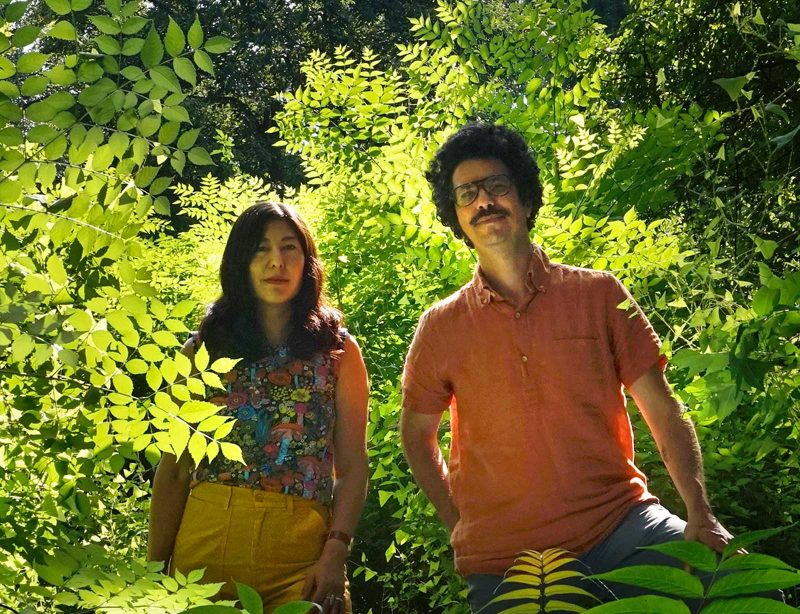

Logan Cryer sits down with Nadia Hironaka and Matthew Suib, dynamic duo of Philly experimental film, and collaborators in every sense of the word- including marriage & parenting. We learn in this 33-minute episode, however, that Nadia & Matt’s collaborative practice hasn’t always been successful- it took time to earn each others trust. But learning to work together ultimately led them to create some of their most iconic works, such as Moon Viewing Platform, and now, Field Companion. Like Moon Viewing Platform, Field Companion surrounds themes of community, but Field Companion points a special focus on symbiotic relationships in mycology. Intentional reveals throughout the film show that not everything is what it seems; Hironaka & Suib say “in the media… it’s getting harder and harder to tell what’s real.”

“Field Companion” is currently on view at Locust Projects, Miami through February 5, 2022, after premiering at Rowan University, New Jersey earlier this year (Sept. 7- Oct. 30, 2021).You can listen to Artblog Radio on Apple Podcasts and Spotify. Thank you to Kyle McKay for composing Artblog Radio’s original podcast intro and outro!

Transcription

[00:00:12] Logan Cryer: Hello friends. You’re listening Artblog Radio, recorded in Philadelphia. My name is Logan Cryer, and in this episode, you will hear a conversation with myself and two artists and collaborators, Nadia Hironaka and Matthew Suib. Nadia and Matthew work collaboratively on films, videos, public artworks, and immersive installations. Their practice embraces research and experimentation, and it encompasses historical facts, popular fiction and creative speculation.

They recently had an installation at Rowan University Art Gallery titled “Field Companion,” which we talk about in this interview. “Field Companion” will also be on view in Miami, now through February 22nd at Locust Projects. We also talk about “Moon Viewing Platform,” an interdisciplinary public art project that was completed in 2019 in Philadelphia.

My conversation with Nadia and Matt begins by asking them about the beginning of their personal relationship and how that led into their professional relationship.

So the first question I have, is I’m not sure- but did you all meet in college?

[00:01:32] Nadia Hironaka: Technically, we met in college. But we didn’t start dating until after you had graduated.

[00:01:39] Matthew Suib: That’s true. Yeah. In the… sometime in the mid nineties, you don’t have to get too specific. (Nadia, Matt, and Logan laugh)

[00:01:47] Logan Cryer: So you met, you dated, and then you started making work together?

[00:01:52] Nadia Hironaka: Yeah, so we, we met in May, I think Matt was a senior at University of the Arts. I was a sophomore, and have basically been together since then. We really just supported each other’s practice for a long time. I went to graduate school right after undergrad, in Chicago. I was there for a few years and then came back and pretty much started teaching actually right away.

Matt was working at the Fabric Workshop and Museum, and so I think his interactions with a lot of artists was happening through that venue, and we started making… we were doing our own separate artists practice at that point. And, but at the same time, working together and often like, supporting one another, critiquing one another.

You know, we then were together for many years, we got married, we still had our separate individual practices and it actually took an outside entity, there was a gallery in LA called Telic Arts Exchange, that proposed we do a collaborative exhibition. They said, “you guys can do two solo exhibitions, but the nature of our gallery is we really loved collaborations. And since we know you guys are a couple, you know, would you be interested in collaborating?”

And it kinda took that outside force to bring us together. Before that I think we had a really tough time collaborating. We would argue– not about the concept, we would argue about how to arrive at a concept. (laughs) So, you know, it was, it was pretty challenging and difficult, and we definitely had, I think very big egos at the time.

And, you know, at some point there was a level of trust that I think just was really secured. And once we made our first project together “The Soft Epic, or Savages of the Pacific West”, we instantly– like, we were like, right on the heels of that– made “Black Hole.” And these two projects were ones that we were really pleased with.

And our working practice was so fluid, and actually really, we both were working on everything. If there was a separation, it’d be like “you do foreground; I do background.” But um, you know, in terms of the filming, editing, all of that, we were doing it together and it was working really well.

So we decided we were going to keep going with that. And still are doing it (laughs)

[00:04:17] Matthew Suib: I think prior to those first two collaborative projects that happened kind of concurrently, prior to that, our longest running attempt at collaboration probably was like under an hour? (laughs) From, from deciding to collaborate on a project to deciding, to not collaborate (laughing) on that project, uh, In some heated curse filled moment.

So it was, you know, there was a big learning curve, learning how to collaborate, like truly collaborate. Not just, you know, “you give me this part of the project and I’ll mash it up together, and that’s a collaboration.” You know, really starting from the genesis of a project and working all the way through the project together sort of on every facet of it.

And it, it took a while to figure out how to do that. And also to understand the value in doing that. And why, why we were able to do it, and why we should be able to do it, which is that we had shared a studio for years and we were, you know, number one fans of each other’s work. You know, we had similar parallel interests, even though our work kind of came from different angles.

Once we realized that, like in every other facet of our lives, we really trust each other implicitly, then it became a lot easier to hear something, like… You know, “that’s a really dumb idea that you just pitched” and say– you know what, instead of getting angry and, you know, concluding this attempt– like, “you actually might have a point there, because you know, not everything I think of is brilliant and maybe I should let go of it.” And, you know, “we’ll find some other area where we can kind of, you know, come to an agreement and move forward and wind up somewhere that we wouldn’t have otherwise.”

[00:06:01] Logan Cryer: Yall, this is so sweet. I love hearing you talk about this (laughs)

[00:06:07] Matthew Suib: Yeah, we’re pretty sweet on each other. I think that we might keep doing this thing.

[00:06:13] Nadia Hironaka: Yeah, we’re gunna stay together. (laughs)

[00:06:14] Logan Cryer: You were talking about collaborating. I mean, with the two of you, but it also seems like collaboration with other artists is a big part of your practice as well. Like, I know Eugene Lew is someone you’ve collaborated with for, I mean, over 10 years? Maybe more, I don’t really know?

But is that collaboration, do you think that comes from having kind of a film background where it’s a little bit more collaborative than a visual arts background? Or is it just, this collaboration works so well, you were like, let’s bring other people into this. How did you get there?

[00:06:46] Matthew Suib: Yeah, the latter. Yeah, the film background, I mean, you know, so much of filmmaking is thought of as, as collaborative practice, but Nadia’s background with film is super DIY. I mean, literally, you know, just her with the camera. Her in the edit suite, you know, when she was working with film and then, you know, same with video.

And yeah, really, I think what that came from– the invitation to other collaborators to work with us– came out of our success with our early collaborations or at least what, you know, how we felt about it, which was that is was a really positive step forward, and that the work was something that was, you know, sort of beyond what we could do on our own.

And that, you know, the, the other thing I should mention– just stepping back a sec, talking about like trusting each other’s judgment– you know, is that we being so familiar with each other’s work, the criticisms that we would often sort of discuss with each other, were ultimately things that were like– if we’re being really honest with ourselves– were weaknesses, you know, in our practice, that we just sort of couldn’t see or couldn’t acknowledge.

And so what comes of that is that we wind up focusing on the strongest parts of each other’s work, and… felt really good about that. And so we immediately turned, you know, to people who we admired and maybe had some relationship with. And started to invite people, you know, that we kind of thought of as like-minded, and– often musicians and composers– who have one foot in the kind of visual art world too, so that they’re already kind of conversant, we’re conversant in experimental music, and so, you know, we kind of hit the ground running.

[00:08:31] Nadia Hironaka: Yeah, and I think it’s funny- with Eugene, so, I actually got a Pew Grant a long time ago in 2006. And I, during that year, I met some really great folks who were also my year. And I think it was maybe only like a year or two after that I proposed a collaborative project. This was actually before Matt and I were working together.

Um, And it was with a dance group, MiRo, and also Eugene. So I invited Eugene and we did this project called “Principles of Uncertainty,” we had a little short-term residency at Fermilab outside of Chicago to study the patterns of neutrinos. And it was, you know, very fun and complicated, but I, I think I have always really enjoyed the collaborative nature of work, even though, as Matt said, it’s not like my art projects in the past were very collaborative, though.

It really was just me doing everything. I think at some point, you know, I became a little bit more, at least mature in my practice and realized, “Oh, I can’t do everything (laughs) you know, I really need to expand this a little bit more and bring in some other folks, who are experts, and sort of masters of, you know, in their, world, and see if there’s some, like-mindedness where we can work together and really develop, you know, great, awesome concepts.”

I mean, for Matt and I, you know, it’s definitely, we, kind of do the same thing. So for us, it’s important from beginning to end to kind of be involved. I think when we bring in other collaborators, that can change sometimes. And sometimes there’s people who, you know, might be working on just one facet. Sometimes they’re working on the whole project and alongside with us, but it really, it opens up our eyes and sort of our way of thinking about the artwork that is being made. And it also allows us, you know, to, as a group, like the larger group, to benefit from each other’s, you know, skills and our strengths, for sure.

[00:10:21] Logan Cryer: Yeah, like, in terms of… when you’re talking about the cloud of nature, something that kind of sparks for me is thinking about your work and how so much of it is about ecology and the way that nature kind of works together with itself. I mean, with your piece at Rowan, “Field Companion,” I feel like that is, it’s a video installation that immerses you into these poetics of all of those systems and how they’re working together.

Something that I noticed in the exhibition text is there was mention of kind of how the pandemic was shifting the way that you were thinking about your work, particularly exploring The Pine Barrens in New Jersey.

But I’m curious if you could talk about that a little bit more of what shifted for you when lockdown started, and how, if at all, that affected the final piece?

[00:11:15] Nadia Hironaka: So, you know, with the pandemic, I think everyone, I know their priorities shifted and changed. And the, activities obviously that we were used to doing also really shifted and changed. And I think for a lot of people, this was a, you know, obviously a bit of a depressing time and also, a time to kind of… you know, evaluate, like “what do I do with my time? What’s important?” You know? And I think for all of our friends who were making artwork, it was a really tough time. Like, nobody felt motivated to make work. It just… like it just, you felt like, “well, I’m going to make it, and then… what?” You know, “I’m not showing it anywhere and what’s going to happen?”

And, you know, we were all doing zoom meetings, like crazy. It just, it just had a real sense of everything kind of came to a halt. And we were, I think Matt and I were definitely like, “okay, what do we do for activity, to entertain ourselves, and to keep up a little bit of like, you know, still fun and excitement?” (Even though our, you know, art activities and our social activities have definitely kind of come to a halt). And I– well, we both– have always loved the outdoors and hiking. And our daughter finally, I think it was at an age where she could tolerate a hike with us (laughs) that took some time. But we had just started, I think it was maybe only like the year prior, to begin this kind of like diving into mushroom foraging and the beginnings of mycology..

I will claim, I don’t know if you’ll disagree, but I will claim this comes from my love of looking for four leaf clovers. (laughs) I love looking for four leaf clovers! It’s like, it’s sometimes hard to walk by a big clover patch and not stop. I think Matt was joking at one point, like, “you should, you know, if you love this so much, you know, why don’t you, you should look into like mushroom foraging, cause that way, like on hikes and stuff, there’s something you’re looking for.” And I’m like, “that’s a great idea. I will.”

And of course, funnily enough, we both, you know, got very into it very quickly and had a great time. We were up in Maine back in 2019, in the summer, doing a short little residency there, and just really got to explore and see some interesting mushrooms that we weren’t familiar with, and that was just continuing on.

So then when the lockdown happened and everybody was kind of stuck inside, we wanted our daughter, especially, who at the time was nine, to have some activity and be able to go outside. So we just started going really regularly, you know, probably every other, every three days out for a hike.

And it didn’t matter if the weather was nice or if it was raining or snowing, we just kind of went out and we used mushroom foraging too, as a way, that… You know, I think when you’re starting to do some reading and stuff about mycology, and thinking about– not just like a hike, you know, where you’re, you have an end destination, like the end of the blue path or the red path, or, you know, whatever, but– like, okay, let’s just get out there and start looking, you know, and it is, there is a funny way people who do mushroom foraging, conduct a hike. Because you’re constantly looking down at the ground and you’re constantly looking you know, around you. And you kind of start spinning off in these little circles off the path, but it was that sense of adventure of like, kind of like a treasure hunt, and trying to find something that I think all of us, and especially our daughter, just kind of enjoyed and gravitated towards. And it, it definitely was a different kind of experience for us enjoying the great outdoors than we had before. It was, you know, very much about this looking around and spending time in a space and not so much about moving forward and trying to reach an end destination.

[00:14:57] Matthew Suib: I think the shift that you’re talking about though in, in the work it actually goes back before the pandemic began. And… the themes of “Field Companion” kind of come from a previous project called “Moon Viewing Platform.” Not come from that, but they… we started to explore them in that, in that piece, and were pleased with it and wanting to kind of continue thinking about ideas of community and what’s valuable in the community, and what’s shared in a community, that eventually got us to “Field Companion.”

But I, for me, the impetus or part of it at least was the incredibly hot and divisive and cynical kind of sociopolitical climate that we’ve all been struggling with for, you know, the past at least five years now.

And you know, I think we can, we can think about it starting in 2016 and, you know, I think you can put a pretty clear start point, you know, around the beginning of the Trump administration. And we were invited to do a public art project, a large-scale project with Mural arts in the… some point, you know, midway through the Trump administration and… you know, our gut instinct was to kind of just put a giant F-you sign on the side of a huge building, you know, as large as we could make it.

And you know, we had to check ourselves, you know, we… Our work has, in the past, often engaged political themes and current events and has been responsive, sometimes in the moment, really, as things around, you know, as events are unfolding. But we wanted to step back and not, sort of, spiral into this kind of cycle of, of discourse that was, you know, in some instances incredibly necessary, and you know, long overdue, but… If we were going to dwell in, you know, our creative space, you know, thinking of new ideas and putting something into public space, particularly a large scale public art project, we didn’t want to echo that, you know, the, the vibes around that kind of discourse, you know, endlessly throughout the city. And instead we thought about, you know, what can we put in front of the public that is, you know, represents something that’s common and shared, and that can, we can think of maybe as some sort of model, or models, you know, for you know, for what makes a community, and what brings people together?

You know and, we made a garden, and we made a film. The garden was this you know, city block- long, neglected public space that we converted into this garden based on a fairly ancient Japanese farm of Gardening called kare-sansui, which is dry landscape garden, rock gardens they’re often referred to as. And made that garden as a film set, and a viewing garden.

So it was viewable, not enterable- for all sorts of public art insurance, liability insurance kinds of laughs) but we had always intended for it to be a film set too. And so we filmed with a group of local artists, musicians, activists, kids in the neighborhood, friends of our daughters, and our daughter… So people in our immediate community, people that we admired. There was Christina Martinez, who is the chef and– internationally renowned chef– and owner at South Philly Barbacoa, who’s an undocumented immigrant, and incredibly active politically in immigration issues; Harold E. Smith, who is a legendary free jazz drummer, semi-retired, but sort of… you know, he’s done some very seminal jazz recordings and he’s also a practicing healer now, and so he’s in the film; and Sarah McEnany, who’s a painter and visual artist, and also is is one of the people responsible for the existence of Rail Park in Philadelphia, ( this project developed under the auspices of Mural Arts and Friends of Rail Park, and it was related to the development of Rail Park).

So, you know, there were people that we admired who are doing creative work, neighbors who are just engaged in their communities. And they’re all engaged with this garden and the moon is constantly visible, you know, over the garden. And that’s sort of this common point, you know, that everyone– not just in our neighborhood or our city, but you know, anywhere– kind of shares. And all of the kind of metaphor potential that comes with that image.

[00:19:39] Nadia Hironaka: And then like taking that idea of bringing the physical community all out together to a large garden space to kind of celebrate the moon and all the community work that that was happening. I think both where we were, but also nationally across the country, because obviously in terms of politics, it was really the community, kind of coming together that did so much, I think, you know, in terms of changing a lot of local minds, and kind of getting politics moving, you know, slowly, but in the right direction.

For “Field Companion,” we couldn’t bring the physical community together (laughs). So we had the challenge of, instead of working on the large scale, we’re like, “okay, let’s work on a very small scale, but to talk about some of the same ideas that we were really interested in about what fosters a community, what fosters an environment, how does growth happen, how do all these things work together?”

So for “Field Companion” we built a terrarium. So the terrarium is pretty small, you know, I mean, it’s not gonna be a big terrarium, but a, you know, pretty small piece, about three feet by two feet and look to, you know, some of the interesting plans that we thought The Pine Barrens seemed to work really well for, creating, you know, that terrarium space. And then use that as a set, just in the same way we use for “Moon Viewing,” we use the abandoned lot as a set, for “Field Companion,” we used our terrarium as a film set. Where we then, of course, placed in most… some animals were actually, (and creatures) were in there, but most were placed, you know, digitally, into that space, in order to have this like larger thematic conversation about, how it all works, why it works and what their part is. You know, in terms of kind of having both some autonomy, but also having some, you know, activation, in terms of having that community grow and develop, and species to continue within that space.

[00:21:37] Matthew Suib: Without geeking out too much on the mycology aspect of it. You know, we, as our interest in mycology has grown over the past few years, you know, we’ve read more and more about it and there’s this whole body of research that’s been developed over, probably the past 40 or 50 years, but a lot of it in the past, I don’t know, 10 or 20 years that is looking at how fungus and mushrooms connect all of these organisms within a forest environment.

And so, you know, as we were kind of thinking about what was you know, what we were finding some joy in, you know, with our pandemic experience, you know, where we were able to find that, sort of peace and quiet, and concentration and focus, it also so happened that it sort of dovetailed with these things we’ve been thinking about with “Moon Viewing Platform”, you know, about you know, what kinds of relationships are valuable in the community? You know, what kind of relationships form a community? You know, and here we’re reading, that mushrooms are contributing to the survival of, you know, all sorts of species, in the forest and… but they’re, you know, also the, the, the entire range of, of roles, you know, are being played by this as well.

So it’s not, it’s not like a it’s sort of fantasy land view. It’s very real world, but there’s you know, there’s mushrooms that are parasites, there’s mushrooms that have very symbiotic relationships, there’s mushrooms that have critical collaborative, survival relationships with other organisms. They don’t, you know, these mushrooms can’t exist without other organisms.

And for instance, lichens are, are two organisms, a fungus and an algae that don’t survive without each other. But most people think of them as just the single thing. In fact, it’s, you know, to think about it really shifts some perspective, which is another thing that was happening in our own, thinking over the pandemic was, you know, shifting perspective and trying to like pull back and not focus on like the, the minutia and the, the intense issues around the pandemic and the politics at the time, you know, but to pull back for perspective and, and take a breath and say, you know, what, what kinds of connections are important and valuable?

[00:23:49] Logan Cryer: To that point of taking perspective, something that’s aesthetically really interesting about your work is at times things look real that aren’t, you know, quote unquote real, or things that are real look, like they’re edited. Is that kind of conflation between reality and fantasy? Is that a way just to imagine things that are hard to conceptualize otherwise? Is that an aesthetic preference that you all have, and it’s just kind of a fun thing to do while you’re editing and figure out how to kind of get things to that, you know, kind of uncanny place?

[00:24:24] Nadia Hironaka: Yeah. I mean, there’s this notion of the reveal, I think for a lot of a lot of artists. And I think we are definitely artists that are interested in playing out that notion of the reveal. Which means, you ultimately want your audience to kind of be clued into what you’re doing. So, you know, it’s one thing to kind of fool or trick your audience and get away with it, and have them enjoy the piece, but how it’s even cooler, if you can, you know, have the audience understand that you’re fooling them or tricking them for a point, and for a purpose, and to have them enjoy it, you know, regardless.

So for us, you know, there’s something about we want, you know, I hope that the audience are very sort of savvy viewers and so that they understand that there’s manipulation going on. Not just obviously with our work, but that with any, you know, anything they’re seeing really that it can be, it’s all subjective, you know, and that it’s all manipulated.

And that can be okay, but understand that it’s possible. And then once you kind of get over that hurdle, okay. What can happen with that? And so can you enjoy the work, even though you realize, of course it’s manipulated. You know, so for us, that’s, that’s important. It’s to kind of create the magic and destroy it at the same time and still hope that the audience loves it.

[00:25:45] Matthew Suib: Yeah. And collage has kind of been a very kind of operative form for us. Or, inspiring form for a long time. I mean, we for me personally, I I’ve always loved collage. I remember going to MoMA in high school and being really excited to see Monet’s waterlilies, but then being completely floored by this collection of Romare Bearden collages that they had on display it I’d never seen.

And it just, I was, I was so blown away. And I think ever since then, I’ve been really like, it barely matters what it is. I just love collage, that kind of juxtaposition and the combinations of things. And in particular, also this line in a lot of collage between, you know, creating this, this kind of believable space from very disparate elements.

But you’re also very aware of the scenes, you know, where things overlap and where they’re joined, where they wouldn’t normally, you know, in real space. And so. That kind of plays out in a lot of our work where you know, there’s this line between a very plausible kind of space or image. But typically, you know, there’s, there’s a spot where you can see a scene or there’s a loop point that if you watch closely, like you can pick up on it, but we kind of, we kind of liked that line where you can become immersed, you know, in what is the semi plausible kind of space.

It doesn’t, you know, if you step back for a minute and you kind of, you realize that it’s been constructed, it’s fabricated. And you know, that also has a lot to do with where we are you know, in a capital H historical sense with image-making, you know, and in the media, you know, studio, film, and you know, it’s getting harder and harder to tell what’s real and that, you know, the whole idea of deep fakes is something that I think about a lot as we’re creating these kind of parallel universes, digitally, you know, and like, where does, where does our work fall in there?

You know, it’s art, it’s not, we feel like there’s, there’s not the same ethics at play, but are, you know, they’re there nonetheless to consider. So we, we think about that.

[00:27:53] Logan Cryer: Yeah. In terms of talking about like the medium and kind of the limitations of it shaping the way that it comes together… And I know this is a big question, so hopefully this isn’t like, too overwhelming, but having worked in video for such a long time, I mean, obviously not only has the technology changed, but the way that people individually have relationships with film and video has changed, like, so drastically, even in the last like five or 10 years.

Looking ahead, how are you thinking about how those changes are developing and how your work might follow or react to those shifts?

[00:28:32] Nadia Hironaka: I don’t know, I don’t really see a problem. I mean, I think, you know, one thing to consider as the technology shifts, and changes, and constantly is evolving, is… You know what we, we will technically be doing, and if it’s something that sort of technically gets beyond us, we’ll probably have to hire, you know, or work with somebody.

But I mean, there’s still like some forms of technology- I still have projects that I will really want to do, but the technology doesn’t exist yet (laughs) So I’m not, I’m not sort of adverse to, you know, the expansion of the world of moving images. In fact, I think it’s really exciting.

Sure you know, what Matt was talking about, you know, kind of entering a scary world where people believe everything they see, especially when it’s presented in a manner where it’s supposed to be, you know, quote unquote, you know, true or fact, I think that gets really creepy and scary and murky.

And that, again, that notion of the reveal is why as artists, we are constantly trying to say, like “Look! Don’t, you know, it’s not so much about believing everything you see, just because it may look perfect or it may look as seamless. That’s not the point it’s, it’s been manipulated probably. And that can be okay. Just be aware of it, you know, so that it doesn’t sway your opinion too much just because you’re like, ‘well, I saw it and I guess it’s real.'”

[00:29:52] Matthew Suib: And we also, you know, we, I mean, by definition, we’re very intimately engaged with technology in our studio practice. And of course, as human beings in, you know, 2021, we’re all very engaged with technology on, you know a minute by minute basis. But, we’ve, for a long time, I think, been of the mind that we don’t want to get… like if- when we’re using something that’s sort of beyond, you know, the kind of technology that is accessible to everyone, or it’s something that’s a little more specialized for filmmakers that we try not to get wrapped up in that because you know, we want to bring an idea out using that technology and not have the technology be the focus of it. We dabbled with interactive work, or generative work, for a period of time and ultimately, like kept deciding that everything that we were trying to do was just about that interactive technology and not even about the ideas that we had sort of started with.

So, you know, on the flip side of that is that, you know, the things we carry in our pockets. You know, every one of us can make amazing films, you know, and, it Academy Award nominated films, and amazing art, and they are used for that. And so that’s kind of encouraging and inspiring and, and, you know, somewhat democratic.

I mean, if you think about, you know, the, the lock that Hollywood Studios, you know, had on the film world for so long, I mean, that’s very different now. Of course, it’s, you know, there are still many people who are excluded from using, you know, technology that, that we might take for granted. And so trying to be aware of that, but you know, we, we try to, you know, make something that is… I mean, we love cinema and we aspire, you know, in some ways to that aesthetic, but, but we like to do it with, you know, at a small scale and with people that we know and that we like to work with and other collaborators who are like-minded and really have ideas to bring to the table and you know, not make it about the gear, or the tools.

[00:31:55] Logan Cryer: Hmm. Well, I don’t think I have any more questions. Can you talk a little bit, I guess, give a quick plug to, your show’s going to be in Miami… now? Or in a couple of weeks?

[00:32:08] Matthew Suib: Couple of weeks, we’re going down Thursday to put it up. And yeah. So “Field Companion” is going to open on November 20th, at Locust Projects in Miami, if you haven’t been to Locust Projects, It’s an awesome space. I think that’s been, probably, our most visited spot over the years in Miami, because they always have interesting things going on.

It’s kind of like, holds this kind of institutional ground, like Vox Populi, maybe, in Philadelphia where it’s been around for quite awhile. It’s was started by artists, It’s become, a bit more of an institution. And they’re always, you know, they’re still firmly rooted in experimentation and you know, work that that needs to happen maybe outside of the most commercial context.

[00:32:54] Nadia Hironaka: And that show will run (laughs) sorry, ” Field companion. will run at Locust Projects, opening November 20th and then it will be up for Art Week. So folks are going down for Art Basel, for Art Week, and all the fairs, check it out. And actually it’s going to continue, it’ll run through February 5th. So there’ll be some additional programming that will probably happen as well with that exhibition in January.

[00:33:19] Logan Cryer: Cool. Thank you so much.

[00:33:21] Nadia Hironaka: Thanks!

[00:33:21] Matthew Suib: Thanks, thanks for the great questions Logan!

[00:33:24] Nadia Hironaka: Yeah. Thank you, Logan!

[00:33:26] Logan Cryer: Thank you for listening to Artblog Radio. Be sure to listen to our other episodes and to check out theartblog.org for more content on Philadelphia arts and culture.