My second day in Miami focused on the Prizm and untitled art fairs. I attended both events with my Canada-based friend Glodeane Brown, arts advocate and blogger at Culture Fancier.

Prizm

Prizm, held downtown, founded and directed by Mikhale Solomon, showcased up to one-hundred artists of African descent from over sixty galleries, evoking revolutionary activism in the art field. Sure, Black artists are presented at the other big events including Art Basel, but this sole experience centered them, gave a spotlight to the underrepresented. Among Prizm’s prestigious advisory committee are Tayyib Smith of Pipeline Philly & Little Giant Media, award-winning actress and renowned art collector CCH Pounder, and mixed media artist Amber Robles-Gordon. Prizm’s eloquent diversity and inclusion statement adds the importance of pursuing “equity in the fine arts and creative industry sector.”

Although art history has taught us that marginalized voices are not worth collecting or archiving as much as their white counterparts, Prizm steps up to ensure contemporary Black voices are seen and heard.

Upon entry, we were given promotional material including complimentary back issues of Sugar Cane Magazine, and freely explored our surroundings. Unlike Art Basel, Prizm has individual areas and rooms reserved for respectable galleries, similar to a college tour with art as the star.

Brampton, Ontario, artist Janice Reid set up a confounding installation— a tribute to trans people entitled ‘Portrait of the Afi.” Beneath four photographs stood a green clothed table that contained vintage photographs in frames of pink and ornate silver, books, plantains, Canadian and American money, a solitary candle, perfume baubles, and a religious statue. In another room, photographer L. Kasimu Harris’s “War on the Benighted” series, a constructed narrative set in New Orleans, featured uniformed students between educational pursuits and protests, young activists-in-the-making. Another surprising series starred famed photographer Dawoud Bey as the lens subject.

MindGallery, an LLC based in Miami, showed a framed flatscreen monitor that became an interactive art piece. Their state of the art advanced technology made it so that an individual can request a generated image based on mood. You simply ask via Siri or Alexa fashion for a specific image. For example, I suggested “girl painting an apple on canvas.” Minutes later, the figure appeared— exactly as I pictured her. I immediately thought about “Star Trek”— how those characters made the Replicator synthesize a meal from thin air. That technology is finally here and emerging forward in the art world.

Aziz Diagne of Aziz Gallerie, a self-taught Senegalese artist based in the Leimert Park area of Los Angeles, has been featured on television programs “Insecure,” “Moesha,” and “The Carol Duvall Show.” Diagne covered his room in massive woodcut prints on paper and on clothing, able to craft bold, elongated bodies with minimal cuts; operating in both black and white and experimental color. Each print work balanced positive and negative space, his chiseled figures surrounded in dynamic iconography calling to Ghanaian Adinkra symbols or Egyptian hieroglyphics.

Krystel Ann Art, a contemporary gallery based in Brussels, Belgium, founded by Guadalupe collectors, Olivier Tharsis and Chrystelle Merabli, hosted a slew of dynamic work. Highlights included Panamanian collage artist Giana De Dier and Martinique born, Parisartist and poet Jean-François Boclé. De Dier’s spiritual compositions on Fabriano paper revealed extreme gentleness to Black women figures taken from unknown contexts to be placed in delicate surroundings, adorned by natural embellishments such as leaf adornments and arched halos.

In Boclé’s “A fruit is a gun” photograph, these words are capitalized and written onto a ripened banana held out into the blue sky, positioned and pointed in a skilled gun owner’s fashion. Boclé presented a politically charged irony as opposed to Rene Magritte’s playful “This is not a Pipe.” While a banana cannot be a weapon, the fruit itself has been harmfully used against poor banana farmers. The banana itself sat on the gallery desk, looking the same as in the still, appearing as embalmed as a body in the morgue.

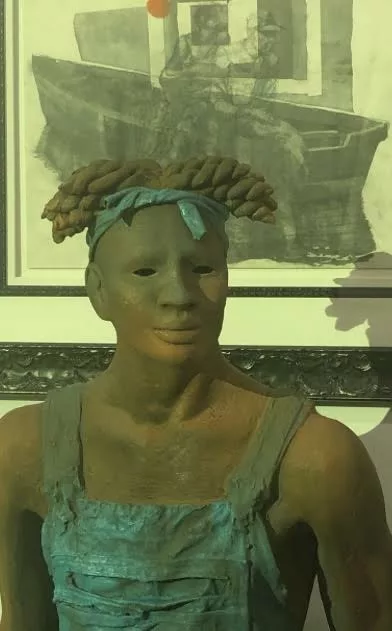

Thus, Prizm provided a revitalizing yet fun and joyous outlet. I appreciated the ample breathing room before entering the next space, that substantial period of time and distance. Nairobi, Kenya’s Tewasart Gallery hosted several artists like abstract figure painters Nadia Wamunyu and David Thuku, Bowie, Maryland’s Overdue Recognition Art Gallery curated Woodrow Nash’s elaborate, pupil less busts and Paul Goodnight’s stylized realistic drawings together, figurative painters Tolulope Daramola Dato and Nii Nortey Hamid filled a solitary room, and Tribal ëyës showcased eclectic African fashion and eyewear.

Untitled art fair

Down to the beach, we ventured, for the chaotically busy untitled art fair— a red tented experience close to the crystal blue shore featuring almost two-hundred galleries, artist-run spaces, and non-profit organizations from thirty-eight countries. Unfortunately, we had thirty minutes to wander through the maze of booths set up similarly to Art Basel. They were closing at five PM. The others ended at six PM.

The School of the Visual Arts Galleries based in New York showed their alumni. Klarita’s “from my hair follicles to my toenails (you love me),” an oil and clay piece on a found bed frame. The piece is titled after Jill Scott’s “He Loves Me In E Flat” off Scott’s poetic debut album, “Who Is Jill Scott, Words and Sounds, Volume 1.” Beyond the pale pink pillows and matching sheets, this stunning work on a queen-sized bed contained a headboard oval portrait of two pleasure hazed faces, the closeness of their realistically rendered heads conveying an intimate joy. The lower part reveals another oval, a clever painting of two pairs of intertwined feet draping out from white sheets. “Holding you, holding me,” the nearby bedside table has a single drawer and atop is “precious jewels,” a small jewelry box containing an oil painting on linen and a lock of their lover’s hair.

Patricia Sweetow— a Los Angeles based gallery— featured an inclusive array of artists. The weight of the metaphor is heavy and strong in Demetri Broxton’s “Hold On,” earth-toned mixed media boxing gloves, employ fascinating materials— hand cut Monetaria caputserpentis (aka serpent’s head) cowrie shells, glass beads, tourmaline points, brass Baule pendants, etc. They hang on the wall, the “Hold On” glove resting on its “My People” twin, the red beaded text activating against intricate yellow and black zigzags. While Broxton’s title may be a play on Eddie Kendrick’s hymnic chant song, “My People… Hold On,” why not include Teddy Pendergrass’s “TKO,” a romantic slow jam comparing love to a “technical knockout?” These gloves symbolize sacred entities not built for a traditional sparring match, primarily inherent in the specificity of the precious materials fusing the artist’s Black and Asian heritage. Pendergrass wants to let it go and search for new love, entailing that through the face of great heartbreak, the fight wages onward. Broxton, however, wants us to stay in love sans our fists, to stay in the realm of good possibilities.

Whereas John Paul Morabito’s huge iridescent weavings combine linen, wool, and gold leaf threads with glass beads, the dangling ends casting strand shadows. The tight, sophisticated pattern at the top acted in an unusual unison with the deliberate looseness at the bottom, both methods of abstraction masterful and meaningful. In reality, Morabito’s evocative curtains nodded to the late Félix González-Torres, an artist known for metaphorical installations of stacked piles that audiences are invited to take away, mirroring life’s vulnerability. In fact, Morabito’s gorgeous essay, “For Félix,” framed the looming beauty as “an aesthetic of splendor and dilapidation where decadently beaded sections are juxtaposed with raw threads to produce visual decay.”

Other quick-sighted highlights included Philadelphia-born, Tyler grad (2018) Autumn Wallace’s glamorous, large-scale beaded ladies displayed at Josh Lilly, a London based gallery and Alia Ali’s enigmatic textile figures situated in fabric backgrounds at the New Orleans based Octavia Art Gallery.

Overall, the entire Miami weekend— Art Basel, Prizm, and untitled— pushed viewers onto the cusp of contemporary international art world reality, teaching us about the artists who may or may not be included into the newer books and essays being written today. These avant-garde spaces engaged provocative dialogues, commanded nuanced perspectives on a creative’s precocious imagination, and challenged the traditional acts of painting, drawing, sculpture, and beyond. In two days, I stood among filled rooms— usually closed and privileged— witnessing an incredible renaissance. Diverse intellectualism and artistic accomplishments by women and people of color were wholly embraced.

I kept gasping in awe at the enthralling spectacles that Art Basel, Prizm, and untitled provided, hoping that prominent curators and collectors wanted to represent these fresh talents for longer than a single weekend. I witnessed more diversity on Miami walls and pedestals than I had seen all year, a woman who traveled to four countries searching for it. The experience momentarily looks to promise real change happening.

Then again, Art Basel alone is twenty-one years old. What kind of momentum has transpired through that time if the art world remains celebrating the same artists way after the event has ended?