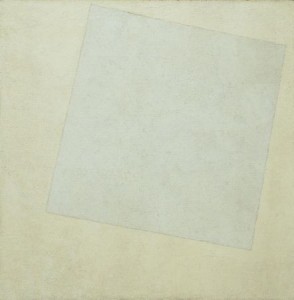

The white monochrome painting, once a joke –”cow in a snowstorm” – at other times a beacon heralding modernism (Malevich’s White on White, 1918) has carved out a serious place in the canon of aesthetics. Nearly every art movement over the last 150 years, if only a shake or a jitter, has paused long enough to produce an all-over, single-color performance. There are thousands of monochrome works dotting the history of art, pointing to a kind of serial of reduction-minded dramas. Stripped down, these works, bold in their simplicity, end up being complex philosophical constructions gesturing to a manifest aesthetic destiny.

So the news from Paris is: white is … the new white! Sort of. Proving that the white monochrome is still in fashion and still relevant, a recent group exhibition in Paris at Marie Victoire Poliakoff’s Galerie Pixi, “Dialogue d’Artistes Blanc sur Fond Blanc autour d’une Tapisserie de Serge Poliakoff.” [Artist dialogue: White on White around a Serge Poliakoff Tapestry] seeks to reinstate the white monochrome, with a sweet, contemporary essay on the subject that stakes out some current notions of the white dream.

The art dealer, granddaughter of the lyrical abstractionist Serge Poliakoff (1906-1969), brought together some three dozen French and European artworks (including one of her own) around a large Serge Poliakoff tapestry, ostensibly the poetic centerpiece of this exhibition. But…it’s not white! An example of the artist’s abstraction in primary colors from 1965 and has little, in my mind, to do with the reason to plunge in here. What is of interest are small and medium-sized works, most no bigger than a fold out map of Paris, all in white or a variation, each eking out ground in the monochrome story. Arranged in what seem to be apothecary cases (in white wood) in this boutique-sized space, the works recall artifacts from an off-beat mom and pop natural history museum.

Brigitte Cardinal’s rectangular clay tablet in off white offering the literal impression of a pair of breasts in a piece called simply “Seins,” French for breasts. Functioning like a relic, or an ancient Greek piece of body art/sculpture, Cardinal’s piece is ready for mass production. The act is simple, effective and, hey! life-sized. One couldn’t help but see the vast time span from the ancient statues of antiquity or even Bernini’s Apollo and Daphne (1622-1625) and its crystalline whiteness – to Cardinal’s piece and its inherent realism.

Alain Frentzel’s approach touches upon miniature painting with four portraits consisting of poured white or off-white paint on vintage wall-papered grounds (all from 2009). Frentzel’s dull white acrylic, dried out and cracked, serves as his central metaphor: The pieces are each called “National Identity.” The critique is not a caustic political one, but the point is well taken and the execution is as the French say “juste.”

Sebastien Kito’s multi-paneled construction in painted plywood with its central form cut out – a large egg shape – echos the sorts of pieces produced in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s when Constructionist Naum Gabo (1890-1977) was all the rage, and artists toyed ceaselessly with unpacking the box. Held together with what appear to be handmade hinges, and somewhat dusty (to good effect), Kito’s work unfolds, sits on a table or floor and doubles as a piece of creative furniture. It is immensely likable and philosophically tight; absence is presence, and presence is multi-layered, visible and invisible, geometric and pure. The piece feels like an object that would have come out of the Bauhaus in the 1930s, an exercise of form in motion; a static object that portends cubist ambitions. And yes, eggs are generally white, too.

Jean-Baptiste Marot’s sculpted and painted clouds, which hang in the gallery front window, are the sorts of illusions that both delight and fascinate in a simple way. Created in a range of sizes, each cloud piece is suspended by fishing line from the ceiling, invoking the entire sky. They are both pieces and wholes (or even holes) – what one might capture making a telescope from your hand and gazing at the sky. Behind Marot’s clouds hang long thick curtains, a setting that induces a puppet show. But these bulbous works are eminently portable: The artist has built specially made valises for each cloud. Crafted in plain plywood with handles and snaps, the sly reference is Duchamp’s “Boîte en Valise” from 1934-1941. Duchamp’s clever “box in a suitcase” contains 69 reproductions of the artist’s work. While Marot’s suitcases for his works were not viewed, I wish they were, as the addition of this element, critical to the foundation of the sculptures lends the work its more conceptual and poetic dimension.

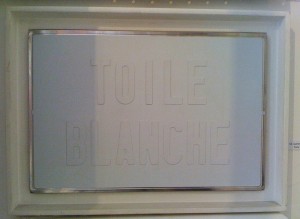

Joël Ducorroy’s strategy is more conceptual with his sign, “Toile Blanche” (White Canvas), a framed and painted object with its sans serif type raised in relief, just a touch above its ground; it reads like a stone license plate with its chrome border. Like many conceptual artists, the stating and restating of the object in-and-of-itself poses a dozen questions all at once, but one that seems to ironically punctuate a modicum of success is: Does it look good?

Ducorroy’s white canvas seeks to explain itself reflexively, stating, “I am a white canvas.” So, to get at the good stuff – Well, then! What of this white canvas business? – the viewer needs to decipher its elements. More than 40 years ago, Joseph Kosuth’s “One and Three Chairs” (1965) sought to to solve the apprehension of the object seen and considered. Kosuth’s art work states its properties, its name and its intentions all in a single sweep of the eye and capture of the mind: A chair, photograph of a chair and silkscreened dictionary definition of a chair are all presented. Kosuth covers all the bases in this descriptive, language-dense work. Ducorroy (born in 1955) produced a white canvas, that in my mind, invites the viewer to examine the execution, and the specifics, such size, texture, language choice and type style. Why? Because this is not a terribly new idea; it’s a variation on a theme. Good aesthetics will nearly always win over the eye and ultimately mind in convincing us that yes, indeed, this is absolutely a white canvas, and a very good one at that! Or…one of the best, or merely adequate. The brand of execution (pun intended) meant to put an end to painting with the soft bullets of words on canvas, is critical. I’m not convinced this is a good version of the idea; Kosuth got there first with an all-encompassing oeuvre. So you really have to make a language-based “monochrome” piece that is, for want of a better word, special, otherwise, we just have more moos in a snowstorm.

Marie Victoire Poliakoff (the art dealer) wanders into the snowstorm, herself, with an ironic little toy bear. Yes, it’s white and its legs, in a nod to the button it wears in its fur – J’aime l’art contemporain! (I love contemporary art!) – she seems to be playing along, asking “Got milk?” It is one of those humorous gestures in a show such as this that winks at the droll ambiguity of the art enterprise. Are we whitewashing a fence or admiring it, or just simply not seeing it? Yes, we love contemporary art – don’t we? – in all its glorious whiter shades of pale.

Monochrome Addendum

Suprematism, Constructivism, Dada (and its offspring neo-dada), geometric abstraction, abstract expressionsim, minimalism, color field painting and a variety of Pop art works have all mapped out the monochrome’s territory. Modernist Architecture is no stranger to the monochrome, either. Think Bauhaus boxes or, more to the point, Rachel Whiteread’s interior casts of negative spaces, like “Ghost” (1990).

And music has a place in this modernist urge. too: John Cage’s silent concert – 4’33” – can be fairly described as a spatial piece; white noise (ambient sound) constitutes its corporeal (and shifting) drama.

Painters and sculptors, however, seemed more able (or quicker to the punch) to lay out the myriad dynamics and high-end Zen of single-color stabs into the corpus of Modern art. Ad Reinhardt’s black paintings are brushless arias soaking up available light; Yves Klein’s trademarked (International Klein Blue) monochromes turned canvases into shamanistic vessels (he did the same in white and gold). In fact, one might even consider Yves Klein’s 1958 exhibition “Le Vide” at Iris Clert in Paris in which he exhibited an empty gallery space – the walls newly painted in white, sensitized by the artist, a perfect negation, an exceptional monochrome. Pierro Manzoni’s white pieces, too, indicated a quasi-Dada and religious content.

Robert Rauschenberg’s “White Paintings” (1951), produced with hardware store-bought housepaint, were meant to serve as screens for the viewers’ shadows. The “Black Paintings” (1951-1953) were to follow, and finally, “The Red Paintings” (1953-1954) ended his love affair with the monochrome. One should note, however, the artist’s true negation of the art surface: the “Erased de Kooning” (1953). Hundreds of erasers were used to wipe the drawing off the face of its support, a willful act of Dada.

Jasper Johns treated the subject of the monochrome in his own fashion with his white and grey flags and targets, while Italian Lucio Fontana slashed his monochromes. Frenchman Daniel Buren produced striped paintings and objects, following perhaps from Barnett Newman’s two-color “zip” paintings.

Frank Stella weighed in with his own stripes and then later purposefully constructed canvases, his lines following the architecture of his zig-zag toiles. Ellsworth Kelley working in the same neighborhood of reductionism produced shaped monochromes as well. Kenneth Noland tossed into the mix his own shaped “chevrons.”

Robert Ryman has notoriously produced nothing but white paintings for decades, a pillar of the minimalist program.

All this to say that white on white is code of sorts for a selection of ideas: death, purity, nothing. Sometimes white denotes good; it is opposed by black, which often signifies the same code selection. White gets “dirty” with bits of darkness; black gets “dirty” with bits of whiteness (or lint, or errant threads or even dandruff if your wearing a little black cocktail dress or tuxedo). Undoubtedly thousands of artists are tempted towards the bare bones monochrome. The blank canvas, with its inherent potential and infinite possibilities, appeals to every artist’s ambiguous ambitions: Everything and nothing.

“Dialogue d’Artistes Blanc sur Fond Blanc autour d’une Tapisserie de Serge Poliakoff.” Marie Victoire Pliakoff’s Galerie Pixi, (Unfortunately you won’t find a catalog of the works online, nor any images of the installation, sorry.) 95, rue de Seine 75006 Paris, France. Tel: + 33 1 43 25 10 12

Matthew Rose is an artist and writer based in Paris, France. His next exhibition, Scared But Fresh, takes place at The Orange Dot Gallery, London, October 6 – 31, 2010.