Leonardo Da Vinci worked with corpses and a quill pen. Mia Rosenthal works with telescopic images from deep space and a Micron pen.

The drawings in Rosenthal’s exhibition Paper Lens, now showing at PAFA’s bright and beautiful Morris Gallery, actually deal with a concept of great concern in present-day particle physics, astrophysics, and metaphysics: the existence of dark matter. They have titles such as “Ultra Deep Field (Dark Matter)”; “Expanding Universe”; and “Nothing to See Here”. And they live up to their names.

Making the invisible visible

This body of Rosenthal’s work, influenced to some extent by the the Latvian-American photorealist Vija Celmins, has emerged from her fascination with images collected by the Hubble telescope, and her experience of the Large Hadron Collider of CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, in Geneva, which she visited earlier this year courtesy of a Leonore Annenberg Arts Fellowship.

Dark matter, for those of us whose knowledge of the subject comes primarily from Star Trek, is the counterpart of matter. Dark matter is invisible and not directly detectable. It is hypothetical, but theoretically, it is everywhere among us. Indeed, it is believed that dark matter accounts for most of the matter in the universe. The search for dark matter is being conducted by astrophysicists, who study things like the gravitational effects of dark matter in outer space; and by particle physicists, who smash protons together in gigantic nuclear particle colliders looking for their subatomic components.

The Large Hadron Collider that Rosenthal visited in Switzerland does not spit out images the way Hubble does. But it is quite an amazing contraption. In fact, it is the largest machine ever built, the heart of which is a 17-mile underground loop that straddles Switzerland and France, and which swirls protons around at close to the speed of light and ultimately smashes them together, replicating the Big Bang in some way. These are the people who seek to discover, or to confirm the existence of, the subatomic particles that make up all of the matter and dark matter in the universe, such as the Higgs boson, the so-called “God particle”. It’s probably also worth mentioning that there has been plenty of drama associated with the process. Indeed, when it was conceived, rumor had it that the collider might destroy the world. To learn more about the collider, take a look at the 60 Minutes piece about the facility.

Bravely, although some may conclude that she is flirting with the impossible, Rosenthal has incorporated her conception of the collider, both what it is and what it does, into her work. In her own words: “It was a challenge to consider how I might make a drawing that incorporated realities of the universe that exist but are not directly visible. I had read a statistic that the makeup of the universe is approximately 68 percent dark energy, 27 percent dark matter, and only 5 percent is observable matter (with a good chunk of that being hydrogen). How might I translate this into something visual?”

When you walk into the exhibition, you feel like you are walking into a planetarium or peering through a telescope or microscope, dark matter perhaps beating in the background. Up close, the intricate craftsmanship in Rosenthal’s drawings is obsessive and astounding and actually painterly. The drawings are brilliant representations and abstractions of celestial and, to a lesser extent, subatomic phenomena: the known and unknown, the visible and invisible.

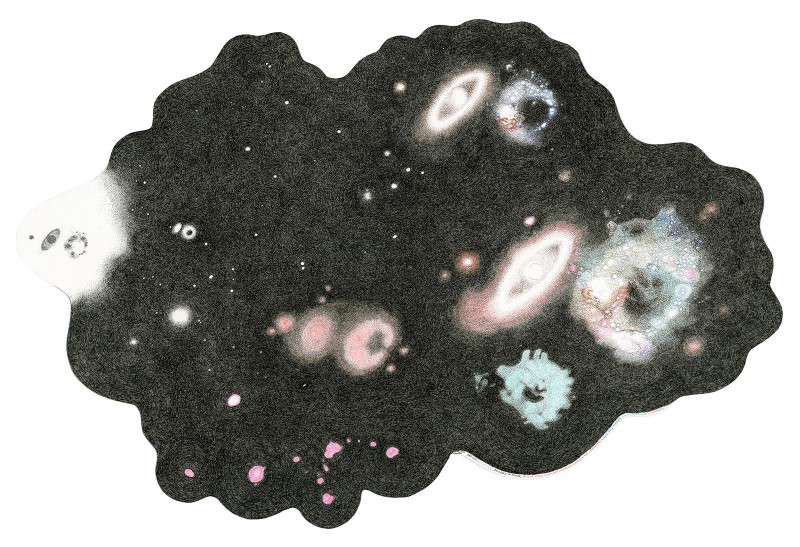

One remarkable note: The world portrayed in Rosenthal’s work here is essentially spherical, mirroring celestial objects (and perhaps subatomic particles as well), and mirroring the actual loop of the collider, and this rejection of the rectangular renders her work almost primordial. A number of these spherical pieces are actually a composite of images from various sources. In “Telescope,” pictured above, for example, there are four rings that are drawn from the center out. The center comes from Galileo’s observation of the moon using a Galilean telescope. The first ring is drawn from a photographic plate from the work of the “Harvard Observatory computers,” in which a group of women who worked in the early 20th century painstakingly recorded star brightness in the photographic slides at the Harvard Observatory. The second ring is drawn from images from the discovery of Pluto. And the outer ring comes from a Hubble telescope image of the Ultra Deep Field. The Ultra Deep Field, as I understand it, consists of stitched-together images of scores of galaxies, some as far as 13 billion light-years away from Earth, which Hubble discovered in an area of black sky.

Rosenthal’s “Arp 147” is drawn from a composite of multiple images of the remnants of a pair of galaxies that collided about 430 million light-years from Earth. As the gallery notes, her rendition of the ways in which Arp 147 have been photographed and interpreted “reveals the beauty that feeds our fantasies of the cosmos.” Of course, this might be said about all of the pieces in the exhibition.

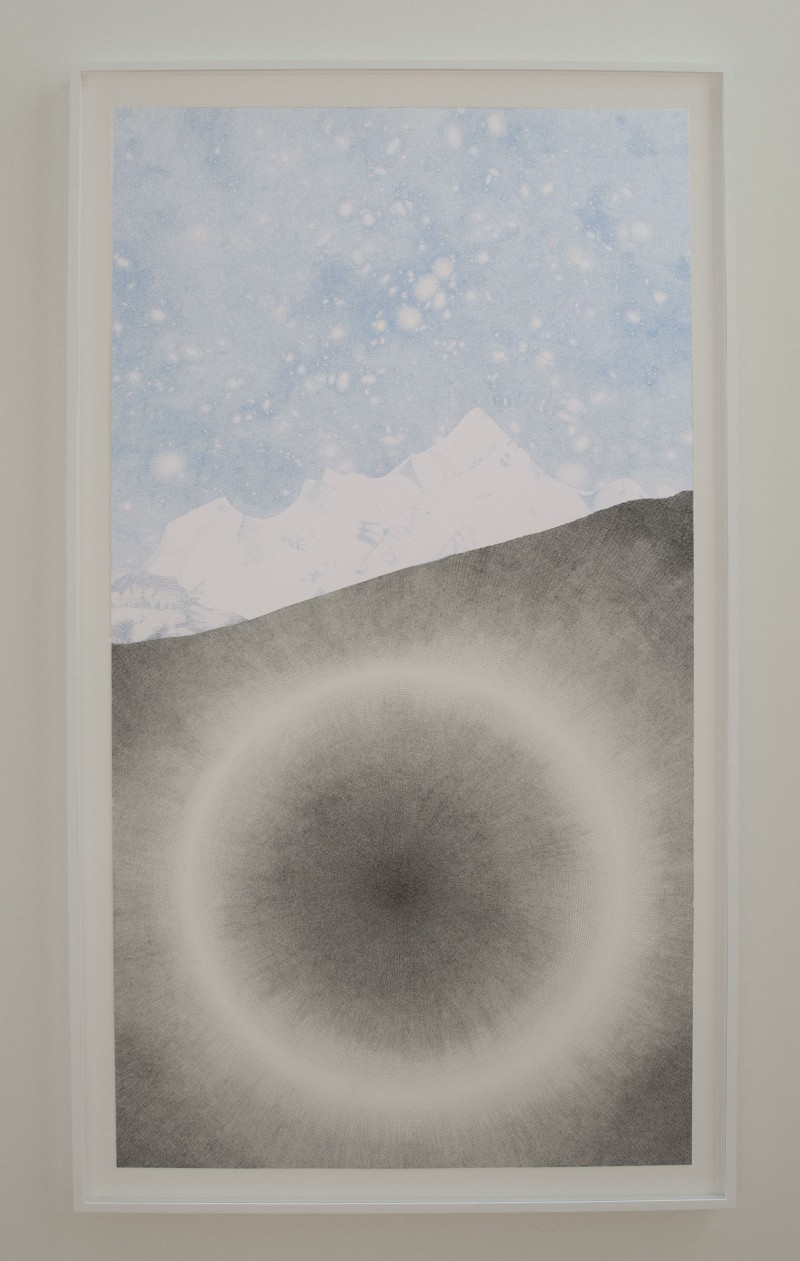

Centerpiece

“Mont Blanc,” which Rosenthal identifies as the piece that brings the whole show together, combines a striking view of Mont Blanc, which is visible from the CERN facility; a Hubble image of the sky that attempts to suggest the presence of dark matter; the spherical ring of the collider; and the collision of subatomic particles. This is Rosenthal’s attempt to bridge the celestial with the subatomic, and I think that she does accomplish that in this stunning piece.

The exhibition also includes a large wall drawing, essentially a performance piece, titled “Expanding Universe,” to which Rosenthal has devoted over 40 hours working in the gallery, and which will be painted over at the end of the exhibition. Although this has afforded the public an opportunity to witness the skill of this artist at work, there is something sad about its impermanence. I suppose its evanescence mirrors the subject matter she is exploring in this ambitious project.

At the end of the day, I’m not sure that Rosenthal has succeeded in her endeavor to visualize something about dark matter, to make the ethereal physical, or to capture the sense of universal time. Her drawing is magnificent, the composites are brilliant, but my sense is that she has not been able to find a way to portray the extremely complex and esoteric concepts she is grappling with here. Ultimately, as I suggested above, it may be that the subject matter is essentially lost in translation, and the result inevitably dispassionate.

By contrast, my impression is that Rosenthal was far more successful in a similar pursuit in her exhibition at Gallery Joe last year, a little bit every day, where she was able to link various natural wonders with a number of mundane objects and images. As Chip Schwartz commented in these pages: “By illustrating what we know directly from our daily lives (laptops, phones, and Google searches) and pairing that with ideas we recognize mostly through indirect, memetic means (astronomy and evolution), Rosenthal confronts us with two very different faces of awareness.”

The theme of the Morris Gallery’s 2015-16 season, which is being curated by PAFA’s Jodi Throckmorton, is: “How do artists make the invisible visible?” In response to this well-worn credo, one is tempted to ask: Is there really anything else that artists do? In the words of Max Beckmann: “My aim is always to get hold of the magic of reality and to transfer this reality into painting—to make the invisible visible through reality. It may sound paradoxical, but it is, in fact, reality which forms the mystery of our existence.” The poets, of course, also contribute to our quest to understand the mysteries of the universe. I am reminded of the last line of Lawrence Durrel’s Justine, the first book in his Alexandria Quartet: “Does not everything depend upon our interpretation of the silence around us?”

I often think about how, due to the ubiquitousness of the Internet, the cell phone, radio, and what have you, most of the planet, including our fragile bodies, is constantly being showered, bombarded, by invisible forms of electronic radiation. Indeed, if these waves or beams or whatever they are were somehow colored and rendered visible, I’m quite sure that our world would go completely dark. So much for making the invisible visible. It is slightly paranoid thinking like this that makes me a writer instead of an artist (or a scientist).

In 1978, PAFA’s Morris Gallery began exhibiting the work of artists living in the Philadelphia region, and ultimately included artists living outside of the area. From 2011 through 2014, the gallery hosted the Bill Viola installation Ocean Without a Shore. With Mia Rosenthal’s exhibition, the gallery is returning to its original mission, with the intention of becoming “a showcase for a diverse array of emerging and mid-career artists from the Philadelphia region and beyond that reflects the pluralistic nature of art-making today.” The plan is to present four exhibitions per year, each relating to a big question or overarching theme. As noted above, the question for the 2015-2016 season is: How do artists make the invisible visible? Artists Emil Lukas, Alyson Shotz, and Fernando Orellana will follow Ms. Rosenthal, each of whom will create new work, often site-specific, for their respective exhibitions.

Mia Rosenthal received her B.F.A. in illustration from Parsons The New School for Design and her M.F.A. from PAFA. Her work is found in various private and public collections, and has appeared in numerous exhibitions. Rosenthal is represented by Gallery Joe in Philadelphia. Artblog’s Rachel Heidenry interviewed her after she received the Leonore Annenberg Arts Fellowship that led to this Morris Gallery exhibition.

Mia Rosenthal’s Paper Lens will be up at the Morris Gallery of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts through Jan. 3, 2016.