The press has not gotten the right idea about Dr. Albert C. Barnes and his thinking, said Kimberly Camp, Barnes Foundation executive director and CEO, this evening at the Slought Foundation. “His ideas were not idiosyncratic,” she said. (Shown, Camp on left with Jeremy Braddock from Cornell, center, and Slought’s Jean-Michel Rabate, moderator.)

This other view of Barnes was not just dreamed up. She got it from Barnes’ papers now in the process of being archived and therefore still unavailable to the public, she said, addressing a crowd of about 40 willing to come out on this weekday night for some intellectual grappling.

Furthermore, Camp said, Barnes’ much discussed arrangements of the art on the walls at his estate were ever-changing. “The ensembles were fluid up until the day of Barnes’ death,” she said (shown, Barnes with dog.)

Furthermore, Camp said, Barnes’ much discussed arrangements of the art on the walls at his estate were ever-changing. “The ensembles were fluid up until the day of Barnes’ death,” she said (shown, Barnes with dog.)As for the education program, the classes at the Barnes changed “180 degrees” in the time following his death from the way they were originally conceived. During his life, artists and scholars were welcome to contribute to the discussions, and discussions is what the classes were. Lectures were a post-mortem wrinkle. “It was a think tank for the love of aesthetics,” Camp said.

Camp’s comments followed a paper, “Neurotic Cities: Barnes in Philadelphia,” delivered by Jeremy Braddock from Cornell University in which he argued that Barnes and his support of modernism was contested hotly by several academically entrenched psychologists, including University of Pennsylvania psychologists Francis X. Dercum (shown left) and Charles W. Burr (shown below right). Dercum and Burr ridiculed the modernists exhibiting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art for degeneracy and lunacy.

Camp’s comments followed a paper, “Neurotic Cities: Barnes in Philadelphia,” delivered by Jeremy Braddock from Cornell University in which he argued that Barnes and his support of modernism was contested hotly by several academically entrenched psychologists, including University of Pennsylvania psychologists Francis X. Dercum (shown left) and Charles W. Burr (shown below right). Dercum and Burr ridiculed the modernists exhibiting at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art for degeneracy and lunacy.

The group were defending their academic turf–somatic causes of mental illness–against Freud, who was already winning his place in psychiatric circles elsewhere.

The group were defending their academic turf–somatic causes of mental illness–against Freud, who was already winning his place in psychiatric circles elsewhere.

In a talk at the Art Alliance, the group of psychologists charged that the paintings were “symptomatic evidence of the insanity of artists,” Braddock said. Dircum said the works showed disease of the color sense and of a great many other mental faculties–direct evidence of neurological deformities–and he called for the institutionalization of the artists.

Barnes, on the other hand, was more in favor of Freud, and in a letter to the Brooklyn Eagle, said the psychologists were “‘old hat'” and called them “‘ignoramuses with a penchant for limelighting.”

The moment was a struggle for cultural power, and Barnes ultimately won that battle, receiving a state charter a year later, in 1922, to create a gallery founded under the principals of modern psychology.

Today’s struggle over whether or not to move the Barnes is also a struggle for cultural power, and sure enough, the charge that Barnes was an unreasonable is part of the let’s-call-the-collector-crazy tradition. Braddock (shown left) made a number of points about how collecting has historically been interpreted as a sign of insanity, so this is just business as usual when all articles about Barnes point up his irrascible side and not his reasonable, intelligent side. (Hey, don’t we all have irrascible moments?)

Today’s struggle over whether or not to move the Barnes is also a struggle for cultural power, and sure enough, the charge that Barnes was an unreasonable is part of the let’s-call-the-collector-crazy tradition. Braddock (shown left) made a number of points about how collecting has historically been interpreted as a sign of insanity, so this is just business as usual when all articles about Barnes point up his irrascible side and not his reasonable, intelligent side. (Hey, don’t we all have irrascible moments?)

Not long after all of this fuss, the Museum of Modern Art was founded. Its method of displaying art has become the norm. But that doesn’t make Barnes crazy either.

As Camp said at the end of her response to this tale from history, “There’s another way to interface with art than [today’s idea of an] art museum”–a white box, with “people shuffling silently as voyeurs.” Her closing sally was, “There has to be more than one contextual framework in which we experience art.”

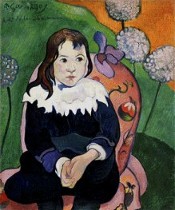

Barnes expressed concern that after he died, his thinking and ideas for the foundation would be set in stone by followers, Camp said (citing the unpublic as yet archives). But he himself was constantly challenging and reassessing his own notions and assumptions(shown, Gauguin’s “Loulou” from the Barnes collection).

Barnes expressed concern that after he died, his thinking and ideas for the foundation would be set in stone by followers, Camp said (citing the unpublic as yet archives). But he himself was constantly challenging and reassessing his own notions and assumptions(shown, Gauguin’s “Loulou” from the Barnes collection).

I buy it. Barnes was open to Freud and he was a champion of modern art, both fairly daring positions in conservative Philadelphia.

I honestly don’t know what he’d think about moving the Barnes collection. But neither do those other people know what he’d think. I say, let’s just move the thing. It’s so inaccessible, I haven’t been there for a gazillion years. Let it stay the Barnes, with its wall arrangements and educational programs, but let’s bring it to the people.

Philadelphians, like the good doctors who said modern artists were certifiable, are so retrograde, they fight every change tooth and nail. If Camp’s and Braddock’s reports are true, Barnes was not like that. He was open to new thinking and new art. Furthermore, the penchant of painting collectors as crazy, one of the points Braddock was making, has certainly applied to Barnes, apparently unfairly. So, let the Barnes change.