The Barry Le Va retrospective at the ICA is a rugged experience requiring intellectual sleuthing and an open mind. But it’s an experience worth experiencing (image, Le Va explaining his work).

The Barry Le Va retrospective at the ICA is a rugged experience requiring intellectual sleuthing and an open mind. But it’s an experience worth experiencing (image, Le Va explaining his work).Le Va (rhymes with ICA) was there, of course, dressed in severe gray silk jacket and slacks, for the opening of this major show. Like his art, he’s not such an easy guy to be around, by turns challenging, gracious, explanatory and gnomic during the member walk-around. I got the sense that he wasn’t too crazy about explaining–he’d explain and then become evasive, uttering something obfuscatory.

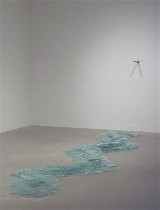

Nonetheless, show Curator Ingrid Schaffner retained her enthusiasm in the face of a steady stream of corrections from Le Va–though it occurred to me that some of her slightly off comments, like daring to mention “scatter art” in the context of his hallmark “distributions,” were meant as deliberate opportunities to encourage Le Va to step in and talk (right, “Continuous and Related Activities Discontinued by the Act of Dropping,” felt and glass).

Nonetheless, show Curator Ingrid Schaffner retained her enthusiasm in the face of a steady stream of corrections from Le Va–though it occurred to me that some of her slightly off comments, like daring to mention “scatter art” in the context of his hallmark “distributions,” were meant as deliberate opportunities to encourage Le Va to step in and talk (right, “Continuous and Related Activities Discontinued by the Act of Dropping,” felt and glass).All this is by way of my trying to give a sense of this work, which is tremendously influential and has a bad-boy undercurrent, a desire to change the terms of sculpture.

First of all, Le Va’s work keeps pushing the boundaries (figurative and literal) of what a piece of art can be or where its edges can lie. He came up against the boundaries early, in the 1967, when the professors who wanted work on a pedestal for the graduate show from the Otis Art Institute (Los Angeles).

This pushing of boundaries reaches its apogee in the ICA show in “Accumulated Vision,” an arrangement of wooden lines and dots on the floor that he projects onto the walls from an imaginary perspective below the floor. He has pushed the art object and the artist himself outside the limits of the room, and he invites us, as the viewer, to figure it out–figure out what he did from where, figure out the relationships (left, “Accumulated Vision”).

This pushing of boundaries reaches its apogee in the ICA show in “Accumulated Vision,” an arrangement of wooden lines and dots on the floor that he projects onto the walls from an imaginary perspective below the floor. He has pushed the art object and the artist himself outside the limits of the room, and he invites us, as the viewer, to figure it out–figure out what he did from where, figure out the relationships (left, “Accumulated Vision”). But though I got the concept–thanks to his explanation–I couldn’t quite get the points of view, imagine though I might. I think he left some facts out here, but I couldn’t figure out what those facts were, at least not on opening night.

And this is part of what makes the work daring (am I arguing for the emperor’s new clothes?), because all along, even before he left the borders of the room, even from the first moment he distributed canvas on the floor and rolled ball bearings on a surface, Le Va’s work has suggested a rationale, a pattern, a plan, and yet it has suggested chaos at the same time. He dares the viewer to make sense of what he has done, to get a sense of how the physical represents some thought, some process that the artist himself experienced (right foreground, glass line detail of “Shots From the End of a Glass Line” and “Cleaved Wall” in background).

And this is part of what makes the work daring (am I arguing for the emperor’s new clothes?), because all along, even before he left the borders of the room, even from the first moment he distributed canvas on the floor and rolled ball bearings on a surface, Le Va’s work has suggested a rationale, a pattern, a plan, and yet it has suggested chaos at the same time. He dares the viewer to make sense of what he has done, to get a sense of how the physical represents some thought, some process that the artist himself experienced (right foreground, glass line detail of “Shots From the End of a Glass Line” and “Cleaved Wall” in background).His pieces are puzzles. They may be artifacts of something that has happened, been thought, been experienced, but to describe them as mere artifacts, as merely residue, is inaccurate because this residue is planned for and exhibited as if it were a thing, an art object.

Le Va used the term archaeology last night at the ICA to describe the art-goer’s process, making sense of the artifacts by projecting back in time to their facture and projecting further back in time to their moment of intellectual conception.

There’s a crankiness here, a desire to confound, an unwillingness to totally please, a willingness to create a puzzle too hard to solve. He distributes voluptuous felt on the floor and then ends the process by dropping glass on top. Crash. The glass was “a period,” he said at the walk-through, referring to a mark of punctuation (see three images above, on the right, “Continuous and Related…”).

For all that, when someone stepped on one of his glass pieces (the noise stopped people in their tracks), he seemed undisturbed, even pleased–by the reactions, by his answer to the question of the inviolability of the art object (it’s not inviolable, and while he doesn’t want you to trash his work, he also doesn’t mind a random accidental disturbance).

If you see the five bullet holes in the wall, you can imagine that the bullets were shot (the deed was done by a University of Pennsylvania Security sharpshooter, after bulletproofing had been inserted behind the sheetrock). The title of the piece left, “Shots From the End of a Glass Line,” explains that they were shot from behind the sinuos line of broken glass. For those of us who watch the nightly news and think that bullets and shattered glass have a real-world presence, this piece suggests how random even fine aim can destroy the pattern of daily life, the order of commerce and its plate-glass windows. I don’t for a minute think this was what the artist had in mind, and even if he did, I suspect he would deny it, because this is not what Le Va’s brand of art is about. As for the broken glass, it was a beautiful shade of bluegreen when arranged on the floor. I would imagine this is something the artist did have in mind, as well as the sinuous arrangement of the glass, the straight shots across the length of the glass line, the pipe target, the noise of the firearm, the noise of breaking glass.

If you see the five bullet holes in the wall, you can imagine that the bullets were shot (the deed was done by a University of Pennsylvania Security sharpshooter, after bulletproofing had been inserted behind the sheetrock). The title of the piece left, “Shots From the End of a Glass Line,” explains that they were shot from behind the sinuos line of broken glass. For those of us who watch the nightly news and think that bullets and shattered glass have a real-world presence, this piece suggests how random even fine aim can destroy the pattern of daily life, the order of commerce and its plate-glass windows. I don’t for a minute think this was what the artist had in mind, and even if he did, I suspect he would deny it, because this is not what Le Va’s brand of art is about. As for the broken glass, it was a beautiful shade of bluegreen when arranged on the floor. I would imagine this is something the artist did have in mind, as well as the sinuous arrangement of the glass, the straight shots across the length of the glass line, the pipe target, the noise of the firearm, the noise of breaking glass.

As for the row of cleavers sunk into the wall about a foot above the floor, handles up, Le Va gave a demonstration of his process of standing, back- to-the-wall, raising up the cleaver, showing the arc that his arm followed to impel the tip of the blade into the wall, and then his repetition of the action a couple of feet further along the wall, over and over. Again, there’s a sound, an action, an idea–and a tactile and kinetic response to these and the materials and implications of the cleavers and the wall.

As for the row of cleavers sunk into the wall about a foot above the floor, handles up, Le Va gave a demonstration of his process of standing, back- to-the-wall, raising up the cleaver, showing the arc that his arm followed to impel the tip of the blade into the wall, and then his repetition of the action a couple of feet further along the wall, over and over. Again, there’s a sound, an action, an idea–and a tactile and kinetic response to these and the materials and implications of the cleavers and the wall.

I liked learning that Le Va did not know about Joseph Beuys’ felt obsession when he started using it in his work. He credited a fellow student who was making banners out of felt. She suggested the fabric to him for both its drape and its edges that do not unravel.

I liked learning that Le Va placed the wonderful “Shatterscatter” layered glass piece on the stair landing both because of its proximity to the windows and because it’s in the way when gallery visitors want to cross the space. I also liked the description of how a single swing from a 10-lb. mallet shattered each of the six layers of glass successively.

I liked learning that Le Va placed the wonderful “Shatterscatter” layered glass piece on the stair landing both because of its proximity to the windows and because it’s in the way when gallery visitors want to cross the space. I also liked the description of how a single swing from a 10-lb. mallet shattered each of the six layers of glass successively.

It’s this physical relationship that Le Va’s work offers–not just the imagining of how it was done, how it made noise as it cracked, how the accumulated pieces impinge on one another–but how the viewer is in a space with things that surround and impede and how the viewer becomes not only a speculator about past causality, but a participant in a new cause-and-effect sequence in the course of moving around and through the work of art.

These ideas may be givens in parts of the art world today, but it wasn’t a given when Le Va first began raising these issues with his work. In fact, it wasn’t even considered a possibility, then.

Also on my list of favorites was Le Va’s use of the ramp–the best ramp piece yet. This space in the ICA has daunted some of the best and the brightest in creating art that fits there. But Le Va’s sound piece is just right, with its tape defining a running track, and the speakers spewing the sound of his running back and forth with 30-second pauses, taking longer and longer to cover the distance. Again, I’m grateful for the explanation, and I do not know that I could have decoded this with the clues given. But it’s a perfect fit.

Le Va said that he liked the sound spilling over into the galleries, reminding everyone of his physical presence performing his task.

I ought to add that part of Le Va’s pleasure in all of this cause-and-effect is focused on how causality can still result in random results–hence each time the 10-lb. mallet hits the glass, the glass shatters differently. Every length run is not exactly the same. All the sculptures, with all their component pieces, follow a plan but have different outcomes as he distributes them. (Right, a photo of “Bunker Coagulation–pushed from the right” from a 1995 installation. A very different version with some similarities, some differences, three photos below, left, at the ICA.)

I ought to add that part of Le Va’s pleasure in all of this cause-and-effect is focused on how causality can still result in random results–hence each time the 10-lb. mallet hits the glass, the glass shatters differently. Every length run is not exactly the same. All the sculptures, with all their component pieces, follow a plan but have different outcomes as he distributes them. (Right, a photo of “Bunker Coagulation–pushed from the right” from a 1995 installation. A very different version with some similarities, some differences, three photos below, left, at the ICA.)

This idea of chance and randomness and following a plan brings to mind John Cage. I suppose then that it’s no surprise that Le Va is also a music lover, from jazz to Schoenberg to Wagner.

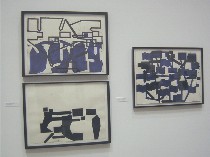

The show also includes notebooks (that seem more like drawings mounted in portfolios) and drawings. The drawings are critical for Le Va’s thinking process and in many ways resemble the pieces themselves, with process a consideration in how they are made (left clockwise from top left, “Part of One/Part of the Other,” 1983, “Plan View for Double-Tiered Sculpture,” and “Plan View for Double-Tiered Sculpture, C”).

The show also includes notebooks (that seem more like drawings mounted in portfolios) and drawings. The drawings are critical for Le Va’s thinking process and in many ways resemble the pieces themselves, with process a consideration in how they are made (left clockwise from top left, “Part of One/Part of the Other,” 1983, “Plan View for Double-Tiered Sculpture,” and “Plan View for Double-Tiered Sculpture, C”). Some of them are beautiful with an energy that presses to burst out of the edges and change shape. All of them seem to be exploratory, and many of them explanatory. They have a plan quality (Le Va was trained as an architect), and are worth some time (right, “Match Tricks,” 1984).

Some of them are beautiful with an energy that presses to burst out of the edges and change shape. All of them seem to be exploratory, and many of them explanatory. They have a plan quality (Le Va was trained as an architect), and are worth some time (right, “Match Tricks,” 1984). There’s also some more recent work consisting of black objects of varied size and shape and their relationships to eachother. This work seems to me less risky, less pushing at the edges. But the contrariness and contradictory contrasts of the early work is still there, pushing internally in the pieces, and not only externally (left, “Bunkers Coagulation”).

There’s also some more recent work consisting of black objects of varied size and shape and their relationships to eachother. This work seems to me less risky, less pushing at the edges. But the contrariness and contradictory contrasts of the early work is still there, pushing internally in the pieces, and not only externally (left, “Bunkers Coagulation”).

If this show sounds prickly, well it is, but it’s the record of a mind grappling with the changes that have swept through the art world since the 1960s, and creating a few of those changes himself.

After I’d made up my mind that I was awfully glad I didn’t have to work with or live with Le Va, he gave a gracious thank you to the preparators and the rest of the crew at the ICA who helped build the puzzle-like piece on the back wall on the first floor, saying they were the best he’d ever worked with. That’s as close as I care to get (right, “9g-Wagner,” 2005, polyester resin and rubber-coated MDF, the piece the ICA crew helped build).

After I’d made up my mind that I was awfully glad I didn’t have to work with or live with Le Va, he gave a gracious thank you to the preparators and the rest of the crew at the ICA who helped build the puzzle-like piece on the back wall on the first floor, saying they were the best he’d ever worked with. That’s as close as I care to get (right, “9g-Wagner,” 2005, polyester resin and rubber-coated MDF, the piece the ICA crew helped build).

However, for all its difficulty, it also has an accessibility, a tactile visual quality that offers another path in.

I’d also like to pass on a final word from my favorite art guard at the ICA. She said that the minute she saw Le Va’s floor distributions, she thought of Polly Apfelbaum’s work. The guard, by now quite knowledgable about the art she lives with daily, said she liked the Le Va show, and she said she double-checked on her theory about Apfelbaum, looking through the ICA show’s literature. She’d hit the jackpot. Apfelbaum’s work, Karen Kilimnik’s work, although they have very different intentions, probably wouldn’t exist without Barry Le Va.

I’d also like to pass on a final word from my favorite art guard at the ICA. She said that the minute she saw Le Va’s floor distributions, she thought of Polly Apfelbaum’s work. The guard, by now quite knowledgable about the art she lives with daily, said she liked the Le Va show, and she said she double-checked on her theory about Apfelbaum, looking through the ICA show’s literature. She’d hit the jackpot. Apfelbaum’s work, Karen Kilimnik’s work, although they have very different intentions, probably wouldn’t exist without Barry Le Va.