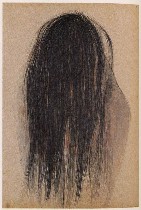

The three shows at the ICA held my interest for longer than usual. That’s a good sign, although it probably has more to do with the volume of pieces–more than 200–in the Richard Pettibone retrospective. But I’ll come back to him in another post (right, one of Berlinde De Bruyckere’s drawings, “Zonder Titel,” watercolor and pencil on paper, the hair suggesting the link between her dead horses and humans).

The three shows at the ICA held my interest for longer than usual. That’s a good sign, although it probably has more to do with the volume of pieces–more than 200–in the Richard Pettibone retrospective. But I’ll come back to him in another post (right, one of Berlinde De Bruyckere’s drawings, “Zonder Titel,” watercolor and pencil on paper, the hair suggesting the link between her dead horses and humans).I thought I’d start with “Springtide,” the most difficult of the three shows, not because it’s bad but because it’s on the edge, raising questions about art and life and comfort zones.

Right out of my comfort zone with the work by Belgian artist Berlinde De Bruyckere, I found myself looking at the third and fourth stuffed horse of the spring art season. The first two from young artists Alex Da Corte and Rachel Frank were female and male respectively. But more important, it seems to me was that Da Corte’s horse lacked feet and Frank’s was lying inert on its side, it’s legs the least powerful of its attributes. De Bruyckere’s horses in “Les Deux” are also on their side, one with stumps instead of legs, and one without it’s glorious tail. And they are indeed stuffed horse hides, not just stuffed fabrics like the other two, thereby ratcheting up the maudlin creep factor.

The pair are stacked in the ICA on sturdy wooden scaffolding that brought to mind the bunks of concentration camps. I took the horses for dead, but even if they are alive, they are doomed–a horse without legs is not much use, after all, and is the antithesis of horseyness, unable to move, carry, flee. And like most horses of fiction, they are stand-ins for humans. In case you didn’t get the human connection, De Bruyckere’s other sculpture, is a woman sporting a sweep of horse’s hair for her mane. She is hiding her front side by curling toward the wall, her long hair hanging down over the front of her body in modesty. She is a deathly shade of gray, and she too has no feet or hands. Her face is hidden. The material is epoxy. A series of drawings expand on this image with the hair, the shame, the nudity, the helplessness.

These pieces are brutal to look at, channeling death and vulnerability. I am at once repelled and intrigued by this work, which brings to mind the grizzliness of religious sculptures, paintings of saints and Christ, and war paintings–all grizzly and casting doubt of the value of life in this world. But this contemporary work holds no promise for the next life. Dead is dead. And alive may not be all it’s cracked up to be.

The is De Bruyckere’s her first museum presentation in America. She was selected for the 2003 Venice Biennale.

Nearby, Erick Swenson’s untitled freezing deer (left), a trompe l’oeil sculpture of a white deer sunk partially beneath a streetscape of ice-coated cobblestones, the frostiness utterly believable, also creates an equation between human and animal, but suggests in its juxtaposition of animal and civilization that we’re just not going to make it (materials, polyurethan resin, acrylic paint, MDF, polystyrene, 276 x 174 x 23.5 inches).

Nearby, Erick Swenson’s untitled freezing deer (left), a trompe l’oeil sculpture of a white deer sunk partially beneath a streetscape of ice-coated cobblestones, the frostiness utterly believable, also creates an equation between human and animal, but suggests in its juxtaposition of animal and civilization that we’re just not going to make it (materials, polyurethan resin, acrylic paint, MDF, polystyrene, 276 x 174 x 23.5 inches).

Swenson’s deer on cast oriental carpets at the last Whitney Biennial seemed out of place and slight in the land of giant wall pieces, but in this context, this deer is poignant. Again, though, the work has a creepy quality, partially because of the hyper-realistic detail of a white creature struggling and dripping with icicles in a somewhat storybook version of our everyday world. A street so coated with ice makes me think of “A Christmas Carol” and has me looking for the rows of quaint shoppes, their names all prefixed with ye olde. I find myself listening for the horses snorting as they pause, pulling carriages down the frosty street. That contrast of all being right with the world (i.e. the romance of the cobblestone street) with all being wrong with the world gives the work its kick. It’s a world where in winter, thin ice can sink and then freeze a deer in the middle of the street, and here amid all the passing humans, there’s no rescue, only a sinking toward death.

Swenson, who works in Dallas, Texas, was born in nearby Phoenixville in 1972. I guess he didn’t like the cold winters.

Compared to De Bruyckere, Swenson’s piece seems so mannerly. But even more mannerly–who’d have thunk it?–is the nearby cloth book, “Ode a l’oubli” or Ode to Forgetfulness, by Louise Bourgeois, now in her 90s. Bourgeois, who also knows how to express vulnerability and the horrors of being caged and helpless and small, is here with a series of fabric pages that button together, each page printed and sewn, a faithful reproduction of vintage fabric from her past. The beautiful bits of fabric bring to mind op art, semaphore flags, bed linens, lingerie, fashions gone by. My favorite ICA guard, Linda, who is an astute observer of the work she contemplates day after day, was chaneling Edna Andrade when she saw all the griddy op sizzle of the Bourgeois fabrics. This piece is relatively tame for Bourgeois, and she was relatively hands off, working with a printmaker and others to create the final product (right, one of the pages, a print with a soupcon of sexual content).

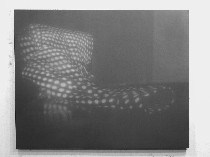

Compared to De Bruyckere, Swenson’s piece seems so mannerly. But even more mannerly–who’d have thunk it?–is the nearby cloth book, “Ode a l’oubli” or Ode to Forgetfulness, by Louise Bourgeois, now in her 90s. Bourgeois, who also knows how to express vulnerability and the horrors of being caged and helpless and small, is here with a series of fabric pages that button together, each page printed and sewn, a faithful reproduction of vintage fabric from her past. The beautiful bits of fabric bring to mind op art, semaphore flags, bed linens, lingerie, fashions gone by. My favorite ICA guard, Linda, who is an astute observer of the work she contemplates day after day, was chaneling Edna Andrade when she saw all the griddy op sizzle of the Bourgeois fabrics. This piece is relatively tame for Bourgeois, and she was relatively hands off, working with a printmaker and others to create the final product (right, one of the pages, a print with a soupcon of sexual content).But the work is beautifully made and conceived. The way the large swatches are framed suggests a desire to repress and encapsulate the vulnerability to past feelings. The embroidered texts of the book–“The return of the repressed,” and “I had a flashback of something that never existed”–also bring into question the reality of what is before our eyes. That ephemeral grip on reality is part of the kick in Troy Brauntuch’s black cotton rectangles, stretched and covered with faint Conte crayon images. The chalk is faint enough to suggest that if you breathe too hard, the image might disappear altogether–making the artwork the thing that is vulnerable. The work’s grip on a reality we can barely recognize makes the whole proposition kind of dicey and vulnerable. Brauntuch, born in Jersey City in 1954, lives in Austin. His images are of things like a checked coat draped on a black, reflective table. The coat, like all coats, is a stand-in for a human being, but is so dematerialized that it’s hard to feel the warmth. All the pieces are hard to decode at first, so the process of looking becomes a process of creating reality out of hints, and the black background suggests a world of film and photography, a world where we increasingly mistake the image for the reality (left, “Untitled,” Emily’s coat on black table, 40 x 50 inches; this image seems more contrasted and pumped up than the real thing, which was not nearly this readable).

That ephemeral grip on reality is part of the kick in Troy Brauntuch’s black cotton rectangles, stretched and covered with faint Conte crayon images. The chalk is faint enough to suggest that if you breathe too hard, the image might disappear altogether–making the artwork the thing that is vulnerable. The work’s grip on a reality we can barely recognize makes the whole proposition kind of dicey and vulnerable. Brauntuch, born in Jersey City in 1954, lives in Austin. His images are of things like a checked coat draped on a black, reflective table. The coat, like all coats, is a stand-in for a human being, but is so dematerialized that it’s hard to feel the warmth. All the pieces are hard to decode at first, so the process of looking becomes a process of creating reality out of hints, and the black background suggests a world of film and photography, a world where we increasingly mistake the image for the reality (left, “Untitled,” Emily’s coat on black table, 40 x 50 inches; this image seems more contrasted and pumped up than the real thing, which was not nearly this readable).

The fifth artist in this show is one of my faves, New York video artist Patty Chang, born in 1972 in San Francisco (here’s a post I wrote on her work at the Fabric Workshop and Museum). Her video “Losing Ground” (right) is projected to an enormous size and seems larger than life, with Chang’s feet at eye level. Chang, who takes on any number of personas in her work, is dressed in a proper A-line skirt. But she keeps losing her dignity as she tries to keep her footing on an undulating “lawn” in front of a hokey backdrop of suburbia.

The fifth artist in this show is one of my faves, New York video artist Patty Chang, born in 1972 in San Francisco (here’s a post I wrote on her work at the Fabric Workshop and Museum). Her video “Losing Ground” (right) is projected to an enormous size and seems larger than life, with Chang’s feet at eye level. Chang, who takes on any number of personas in her work, is dressed in a proper A-line skirt. But she keeps losing her dignity as she tries to keep her footing on an undulating “lawn” in front of a hokey backdrop of suburbia.

I saw this same video in a small screen version, and I much prefer it that way, the small view somehow suggesting the “Brady Bunch,” “Leave it to Beaver” and the “Nelsons,” television’s version of what’s normal. Blown up to fill the ICA wall, the video’s tv references disappear. So does Chang’s practically supernatural fierceness, gone soft and puffy in the larger scale.

Looking at the single Chang video is rather like looking at a single Cindy Sherman, since an understanding of their shape-shifting personae depends on seeing more than one. However, one Patty Chang is better than none at all.

By the way, in conjunction with this show, the ICA has commissioned poetry from Alan Gilbert, Sharon Mesmer, Nick Flynn, and two poets from the University of Pennsylvania, Susan Stewart and Tom Devaney. Their pieces are to be published in a brochure accompanying the exhibit.