Post by Douglas Witmer

[ed. Note: this is the final part of the three-partDouglas Witmer-Linn Meyers email conversation that began Monday, June 20, on artblog. Here, Meyers talks about the physical experience of making her work, accidental and intentional outcomes in her systematic process, and her “direct,” not abstract, art. Read part one here and part two here.]

DW Let’s talk more about the idea of “resistance” you brought up. Obviously it’s something quite physical for you when you are working. The term “excruciation” comes up in the essay from your recent Margaret Thatcher Projects catalogue. I scoffed a bit when I first read that word. But hearing you talk recently about the actual duration of time it takes to make some of your lines, I begin to understand. You need a certain dexterity to perform your work, and there is a bodily expenditure of energy, which may result in fatigue. A magic marker line doesn’t exactly record you starting strong at one end and ending weak at the other like a pencil line might (right, Untitled, 2004, ink and colored pencil on Mylar, 10″ x 11.5″).

DW Let’s talk more about the idea of “resistance” you brought up. Obviously it’s something quite physical for you when you are working. The term “excruciation” comes up in the essay from your recent Margaret Thatcher Projects catalogue. I scoffed a bit when I first read that word. But hearing you talk recently about the actual duration of time it takes to make some of your lines, I begin to understand. You need a certain dexterity to perform your work, and there is a bodily expenditure of energy, which may result in fatigue. A magic marker line doesn’t exactly record you starting strong at one end and ending weak at the other like a pencil line might (right, Untitled, 2004, ink and colored pencil on Mylar, 10″ x 11.5″).LM RESISTANCE. I love it.

When I make the gravity drawings the resistance is minimal; it is mostly a matter of being present and simply mastering the technique. I tape the Mylar to the wall, I stand in front of it with both of my feet flat on the floor, I place my hand/pen at the top of the page, and I draw a straight line by harnessing the force of gravity. Then I do it all over again. The gravity guides my movement, so the only real resistance is the tip of the pen against the paper (and the side of my hand dragging downward against the Mylar.)

About a year ago I started making the horizontal line drawings. There’s A LOT of resistance there. First of all, it’s totally unnatural to draw a horizontal line. Agnes Martin did it with a straight edge, but doing it freehand is another story. So then you’ve got the drag of the pen and the hand, plus the resistance of my body to obey the rules. It’s very exciting. Every moment is like a suspense movie.

The word “excruciation” or excruciating is not really in my vocabulary. I like my drawings to challenge me physically. It’s another way of being awake. Maybe it can be “excruciating” for some people to look at them.

As far as the variation in marks: I think there is probably a lot of variation. Some of it is hard to see for the reason that you already stated — pen doesn’t show that sort of thing as much as pencil does. But the distance between the lines is one way of seeing the variation — it think you can actually see moods in there. It’s almost like an amateur reading Tarot cards though — one doesn’t always know what one is looking at. I’m not sure I can even really re-trace my steps in my own drawings.

Accidents of illusion and line

DW So you were working to get “decoration” and “illusion” out of the work. But there seems to be an incredible illusionism to some of the recent work, which you seem to be really going with. Can you talk more about how and why you allow this?

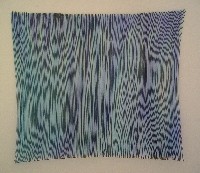

LM As far as the illusion in the cube drawings…that started by accident. I had been making drawings with parallel lines, usually two blocks of parallel lines separated by a small gap. I was taking them down off of the studio wall one day and stacking them on my work table, one on top of the other. The cube thing just sort of happened by accident at that point, and I liked it so I pursued it further. For many years I had avoided the moiré patterns that occur when two or more patterns are layered, but for the first time, with the cube drawings, I felt that that event was working to my advantage (left, “200461,” from the artist’s Gallery Joe exhibit, up through July 2).

LM As far as the illusion in the cube drawings…that started by accident. I had been making drawings with parallel lines, usually two blocks of parallel lines separated by a small gap. I was taking them down off of the studio wall one day and stacking them on my work table, one on top of the other. The cube thing just sort of happened by accident at that point, and I liked it so I pursued it further. For many years I had avoided the moiré patterns that occur when two or more patterns are layered, but for the first time, with the cube drawings, I felt that that event was working to my advantage (left, “200461,” from the artist’s Gallery Joe exhibit, up through July 2).

One of the things that I like about those pieces is that they seem to depict discreet objects, but they really do not do that at all. They are simply sets of parallel lines.

I talked before about the edges of my drawings and how important it is to me that they not seem like a fragment of something larger. Well, with the cube drawings, they really are separate from any thing else around them.

I love the way those pieces float through the exhibition space at Gallery Joe. I don’t think my other works float. That’s something I need to think more about

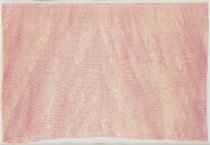

DW I think it’s kind of funny that you so flagrantly break the fundamental rule of Drawing 101: fill the page! But back to illusionism. But I can’t help thinking looking at some of the recent work, particularly the ones with the more “billowing” images, that you are going for the illusion from early on in the process. It doesn’t seem to be a by-product. When you say that in the end the works “do not depict discreet objects” I think you are right in the same way that one could say that all representational painting is abstraction. (Which is to say that I think some of the works DO, to a greater or lesser extent, depict discreet objects.) I wonder, what does allowing (cultivating?) this strident illusionism mean for you at this time? Or maybe I’m seeing something you’re not seeing (right, Untitled, 2002, pinholes in mylar, acrylic, colored pencil, 7.5″ x 7″)?

DW I think it’s kind of funny that you so flagrantly break the fundamental rule of Drawing 101: fill the page! But back to illusionism. But I can’t help thinking looking at some of the recent work, particularly the ones with the more “billowing” images, that you are going for the illusion from early on in the process. It doesn’t seem to be a by-product. When you say that in the end the works “do not depict discreet objects” I think you are right in the same way that one could say that all representational painting is abstraction. (Which is to say that I think some of the works DO, to a greater or lesser extent, depict discreet objects.) I wonder, what does allowing (cultivating?) this strident illusionism mean for you at this time? Or maybe I’m seeing something you’re not seeing (right, Untitled, 2002, pinholes in mylar, acrylic, colored pencil, 7.5″ x 7″)?

LM First of all, I am aware that certain sets of rules (that I use in my drawings) produce certain effects. But the drawings are not composed, which is to say, I may know that the dots are likely to create a billowing effect, but WHEN they billow, or WHERE, is not something that I can anticipate.

On the same subject, I have, over the past few years, made peace with the fact that many people who look at art often allow their minds to draw references within the images that they see. This is something that we learn to Judge in art school, I think.

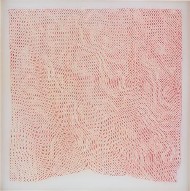

One of the best comments that I ever got about my work was from a woman who came into the studio who had absolutely NO art education. She kind of gasped and said, “Oh, are these pictures of the wind?” (left, “18,945,” 2002, ink, acrylic, mylar, 17.5″ x 12″)

One of the best comments that I ever got about my work was from a woman who came into the studio who had absolutely NO art education. She kind of gasped and said, “Oh, are these pictures of the wind?” (left, “18,945,” 2002, ink, acrylic, mylar, 17.5″ x 12″)

Next, what’s really funny is that I never even thought of that Drawing 101 rule! Honestly. I must’ve missed that class.

To me, talking about “discreet objects” and talking about abstraction don’t necessarily belong in the same paragraph. They are two separate subjects that have an intersecting area.

I know that my work falls into the category of “abstraction” by default, but I really don’t think of my drawings as abstract. (I know you’ve heard this argument before elsewhere, but I cannot help myself.)

Not abstract but direct

DW What I understand is that in this instance you are referring to the image that is produced, not the drawing itself, as the discreet object. So I guess that comes back to the idea of resistance/tension. And now it’s not so much purely visual anymore. It has to do with one’s mind and perception of what is real. Right?

LM You got it. But the bigger question remains, (and I have no intention if having either of us tackle this one,) “what is real?” And that loops back to my point about my drawings not being abstract.

DW Given what you have just said, what would you say is the word or phrase you use describe your drawing?

LM I wish I had a word or phrase to define the drawings that I make. I’ve been searching for a precise and brief way of describing what I do, but I haven’t come up with anything. I like the word “direct.” I really DO NOT like the word “obsessive.” I think it is inaccurate. And I don’t think “abstract” gets to the point either.

I certainly do not make “Minimalist” works. However, maybe they are “minimal” simply because they are rather distilled.

On the one hand it is frustrating to not have a simple descriptive phrase that applies to the work that I do, but on the other hand, those categories can be so misleading, maybe I’m lucky not to fit into any of them.

–Douglas Witmer is an artist, blogger and artblog contributor.

meyers, linn