[This is part 2 of a multi-part article.]

Who are you?

But few young artists get even this far – working for an established artist, let alone getting into a retrospective at a swank well-known gallery. Most become disgruntled at having to create or help produce the work for some artists with little time or energy for their own work. Or worse, they find their own fledgling careers overshadowed by the larger ones they are working to perfect.

In 1986 Paul Hasegawa-Overacker (known as Paul H-O) was an aspiring 31-year-old sculptor working at the Baskerville + Watson Gallery. He was asked to give Sherrie Levine a hand and carry some wood for her from a near by lumberyard. As they were loading the wood, Levine asked H-O if he might “build some things for her.”

At that time Sherrie Levine was the “quintessential post-modernist” for her outrageous and ingenious appropriations of modernist masterworks. She “re-represented” Edward Weston and Walker Evans photographs as her own. She hand-painted modern icons “after” Mondrian or Leger from art book reproductions. Levine tripped the contemporary mirror on art history and her cool and relentless pursuit of this new layering made her the art world’s newest deconstructionist doll. Levine turned the idea of originality in art on its head, and in the middle 1980s her hunger for ever more incisive projects was enormous. Enter Paul H-O.

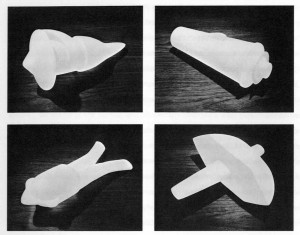

Bachelors (After Marcel Duchamp), 1989.

Bachelors (After Marcel Duchamp), 1989, fabricated by Paul H-O

Levine’s ambitious project was to fabricate Marcel Duchamp’s 1915 Malic Molds, the masculine elements that drive the lovemaking process in the Frenchman’s masterpiece, The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even. This work, The Bachelors (After Duchamp), would be exhibited at the Mary Boone Gallery on 415 Broadway and elsewhere to great acclaim. Over the course of the several years, Paul developed, designed and constructed a series of prototypes for the artist, including chessboard panels and a lead silhouette of Abraham Lincoln’s head. But the Malic Molds were perhaps the most challenging works, as they had to be created from flat painted models and turned into glass sculptures. They took more than a year to produce. The pressure to make them in more than a respectable manner – they had to be perfect – plus the inadvertent realization that Paul had become the “author” of the sculptures made him understand that he “couldn’t remove the Paul from the work.” Needless to say it was confusing and trying. H-O was soon burned out and left his job as fabricator for the grand appropriationist to return to his own “stuff.” But lessons were learned.

H-O’s own attitude towards originality was awakened in a critical fashion. “If Sherrie’s approach is cool and cerebral, mine is decidedly heated,” he said. Nonetheless, Levine did direct curators and dealers to H-O’s studio. Indeed his own career, while he was working in the outsized world of Levine’s, was slowly taking off: A show at the Luise Ross Gallery on 57th Street of plywood “surfboard” sculptures was well received. The wily objects were well crafted and clever but also “projected a primal and sexual turbulence” he said, “in contrast to the coldness of Levine’s works.” The artists’ differences were perhaps most evident in their use of common plywood. Levine exhibited handsome but ordinary sheets of plywood for one famous show; the wooden knots in her works were painted gold. For H-O, plywood represented not a post-modern statement in and of itself, but the language of new housing. With its sandwich edges and knotted face, it breathes and exudes a man-made natural warmth. Wood allowed H-O to create intimate objects ready – with his touch – to perform: His shark-fin topped wood pieces like “Thruster,” with their three skinny legs resting on delicate wheels appeared ready to perform some clever dance. His own Duchampian adventures included wood cases – frames within frames that function like suburban Zen koans. More than mimicking their ostensible art function, they were elegant “machines” or portable exhibits- bachelors on the go.

[Read Part 3 of this multi-part post. And here is Part 1, Part 2 and Part 4]

—Matthew Rose is an artist and writer living in Paris, France. His next exhibition will feature his “Scribble Drawings” at the 20/21 International Art Fair with the Art Vitam Gallery at the Royal College of Art, London 22-25 February, 2007.