Miquel Barceló Domo, Africa(2005)mixed media on paper, 75 x 53 cm, photo courtesy of the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

The Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) has monographic exhibitions on through September 28 of two artists whose work hasn’t been seen in nearly such depth in the U.S. Miguel Barceló was one of an international group of artists in the 1980s who popularized expressionistic, figurative painting on a large scale (and I haven’t seen much of his work since then). Miguel Barceló; The African Work is a survey of work done during the past twenty years when the artist resided for part of each year in West Africa, primarily in Mali. Organized by IMMA director, Enrique Juncosa, the exhibition includes notebooks, numerous works on paper, small and large paintings and sculpture in clay and bronze. All the work is figurative, depicting local landscapes, animals and people yet avoids an orientalist romanticism. Barceló worked mostly in an isolated, inland village and lived as part of the local community, who provided a site for his home and studio.

The ninety works are a bit much to take in, but the best of them are stunning. Barceló’s two-dimensional work is strongest when he employs the simplest means and most modest scale: a palette reduced to earth colors, supports of paper or canvas that appear weathered (he purposely exposed paper to termite damage and worked with the holes), and restrained images of a few, suggestive lines. For some he developed an extraordinary method of handling the paper to produce reliefs whose painted forms bulge out of the plane. Another group of large portrait heads have something of Giacometti’s rare combination of likeness and exaggerated stylization.

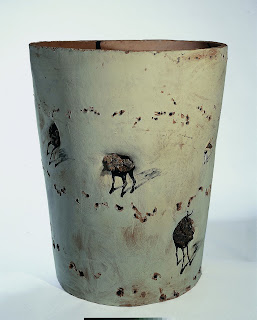

Miquel Barceló Large Pot with Volcanic Rock (Grand Pot aux Scories) (1999) ceramic, 114 x97 cm, photo courtesy of the Irish Museum of Modern Art.

The true revelation of the exhibition were the clay works. Barceló only began working in clay when residing in Mali, which has one of the rare traditions of clay sculpture and architecture in West Africa. Although the artist was taught technique by local craftsmen he does not seem to have derived either forms or handling from them. He developed truly original and extremely powerful works in clay, creating surface imagery of animals and landscapes with colored slips, scored marks, gouged holes and inclusions of clay and rocks. Most of the pieces refer either to dish or vase forms but Barceló has found in them a vehicle to create monumental and timeless works.

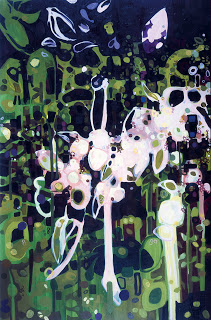

Janaina Tschäpe was raised in Brazil and educated in Germany and New York, where she now lives. Paintings in oil and watercolor, watercolor drawings, photographic and video work including one large, four-channel installation make up the survey, Janaina Tschäpe: Chimera, organized by IMMA curator Rachel Thomas. Tschäpe’s themes are the seduction and danger of beauty and of nature, and she creates her own versions of various mythical stories on those themes (chimeras, mermaids, sirens, and the Brazilian water spirit, lemanja).

The exhibition opens with a room of unadulterated beauty: five monumental oil paintings, the best of which, Lair, 2008, (detail above) is a triptych. They are detailed abstractions with biomorphic forms that refer to or hint at dense landscapes of pre-lapsarian lushness and fecundity. Tschäpe strews the large paintings with small, Klimt-like square or round forms that imply light flickering through a dense forest.

The second gallery contains a grid of photographs comprising 100 Little Deaths (or at least 51 of them, done during 1996-2002). Each depicts a peaceful landscape and reads much like a travel advertisement and they include some recognizable sites of touristic interest (Angkor Watt, lower Manhattan with the World Trade Center towers, a Gothic ruin, a tropical beach). Each image also contains a sole figure: the prone body, usually face-down, of a woman who is often disposed in an inappropriate location (the side of a highway, sprawled on the stairs) so we know she is not resting but instead illustrates the series’ title. Her presence is a bit creepy, but its repetition is such that we begin to ignore the emphasis on violence against women and focus instead on the various locales. It is hard to look at and hard to read.

Janaina Tschäpe, Dani 1, From After the Rain, 2003, Cibachrome, 40 x 50 inches, private collection.

Other photographs, such as Dani 1(above) and the video installation, Blood, Sea (2004) show female figures in natural or acquatic environments; they are dressed in fantastical costumes, often with balloons or stuffed-fabric appendages and trailing hoses, with hands or feet covered by water-filled membranes. It’s not clear whether these odd, hybrid figures are products of the imagination (the artist’s? our culture’s?) or mutants resulting from our polluted environment and disregard of nature.

The myths of Ireland’s Celtic lore have always been intriguing, particularly for visitors from Europe whose post-Enlightenment rationality has banished the traditional means to express wonder, awe, and terror of the unknowable. Tschäpe contributes her home-made myths, and it is up to her audience to decide whether they are threatening or benign.