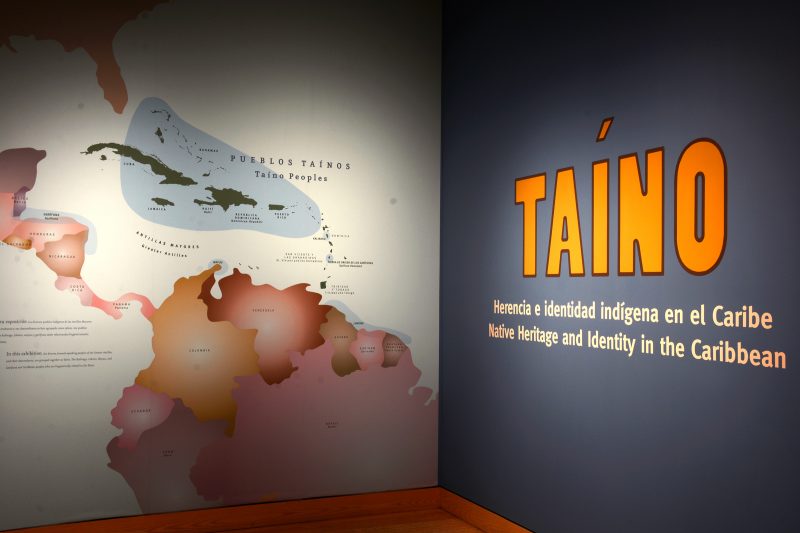

The vitality of Taíno art and culture is on full display in a new exhibition at the National Museum of the American Indian in New York City. Challenging any notions of indigenous life as extinct or vanished, Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean successfully highlights the diversity and tenacity of Taíno presence.

Taíno is a broad term which describes the geographically and racially diverse but culturally blended indigenous people of the Caribbean. (Other indigenous groups, such as Lokono, Garifuna, and Wayuu, also lived/live in the Caribbean and surrounding regions.) This exhibition, which builds a bridge between modernity and tradition, begins with several stone carvings from the Classic Taíno* period (800-1500 CE), including a large and beautiful three-pointed Cemi. Cemi are a diverse class of powerful living objects that take many forms and may have connected people to their ancestors, to deities, or to forces of nature. The one on view here is larger than others I have seen and looks like a landscape with the top point rising up, evoking a mountain. The two humanoid faces carved on the other end-points, likely those of powerful leaders or ancestors, remind us of the spirit force contained within.

Installed near this Cemi is an upright stone slab incised with a simplified human form. This would have been placed with other similar objects around the edge of a ceremonial plaza, or Batey — a sacred space for song and dance, ball playing, and other community gatherings. Further along in the exhibition is a low-back ceremonial stool carved from wood, a Duho, which would have been used by only the most important leaders (Caciques), male or female, for political or spiritual events such as the Cohoba ceremony or hosting a fellow dignitary.

These powerful classical works resonate throughout the second half of the exhibition, which focuses on a group of contemporary Taíno artists who curator Ranald Woodaman considers to be the “tradition bearers” of their culture. A slit drum, or Mayohuacán, made by the renowned Daniel Silva Pagán in 2015, is, in its material, form, and decoration, a modern day version of a Taíno instrument. Pagán’s drum is installed across from a contemporary hammock woven by Leonarda “Doña Esmeralda” Morales-Acevedo. Thought to be one of the few remaining traditional hammock makers, she grows and harvests the Maguey plant, prepares the thread, and weaves the hammock according to customs now thousands of years old. This hammock is a prime example of the endurance of Taíno tradition and of how Native Caribbean objects and words still have life in global languages and cultures. Indigenous to the Caribbean, hammocks quickly became part of global sea-fearing culture after being adopted by European sailors as sleeping places on board their ships.

Taíno people throughout the diaspora carry on the lifeways, materialities, food cultures, objects, oral traditions and stories of their heritage, ensuring the survival of their culture. This is a consistent theme in this exhibition and an important one, especially considering the early and violent contact with Spanish colonizers in the late 15th Century which brutally decimated up to 90% of the Indigenous Caribbean population. People from Africa were in the Caribbean too, forcibly brought to Santo Domingo (present day Dominican Republic) by 1503. Both African and Taíno people were brutally subjugated and violently enslaved but also, at times, resisted through guerrilla warfare, organized rebellions, or withdrawing into rural areas. In addition to the cultural survival that Taíno: Native Heritage & Identity in the Caribbean highlights, Mitochondrial DNA testing has recently confirmed the survival of Taíno bloodlines in the present-day Caribbean.

The exhibition includes a documentary about an ongoing University of Leiden project that considers the diversity of Amerindian legacies in the Caribbean and the cultural exchanges that occurred before and after European contact. Such efforts to support indigenous identities are not new, however, as groups such as the Puerto Rico Taíno Movement, the United Federation of Taíno People, and others, have been working steadily for the last 40 years to ensure Taíno agency in politics, economics, and government as well as in arts and culture. Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean presents the complexities and nuances of those who re-assert Taíno identity in contemporary context — carrying traditional values, knowledge, and a shared sense of history into the future.

*Archaeologists use the term Chican Ostionoid or Classic Taíno to categorize art and objects made by Taíno craftspeople between the years 800 and 1500.

Taino: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean, on view July 28, 2018 – October 2019 at the National Museum of the American Indian, Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, One Bowling Green, New York, NY 10004.

In New York and hungry for more indigenous art, including work by contemporary Taíno artist Jorge González? Visit Pacha, Llaqta, Wasichay: Indigenous Space, Modern Architecture, New Art, on view at the Whitney Museum of American through September 30.