As I write these notes on Pat Steir’s new waterfall paintings, it has recently been discovered that, due to the melting of the glaciers, a hole has developed beneath the surface of Antarctica that is nearly the size of Manhattan. What had sustained itself as solid ice–across more time than I can imagine–is fast turning to liquid, seeking lower ground, and vanishing. All is melting, dripping, falling away. So my thinking about the drips and dribbles that make up the eleven hauntingly dripped Steir canvases, on view at the Barnes through November 17, is weighted by this newly reinforced awareness of the fragility and transience of all things.

Subverting the drip of abstract expressionism

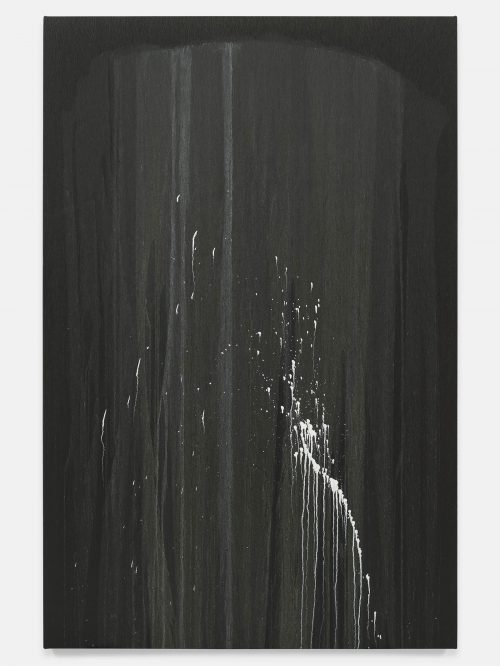

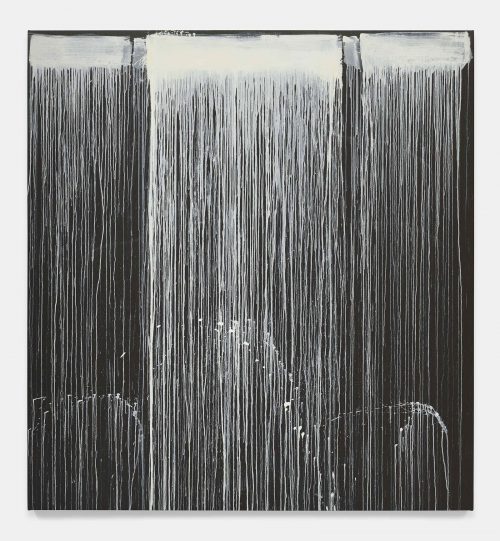

The drip, which is the sponsoring idea, image, technique, and conceptual maneuver of Steir’s Waterfalls had perhaps a less harrowing origin when she began the series in the 1980s. Then, she deftly appropriated the cryptic and emotive sloppy brushstroke that was the calling card of abstract expressionism and allowed it to assume a new iconic status, as the figuration of a waterfall. Suddenly, the hot, high modernist work that was too inflamed with being something to be of anything had a cool, friendly way of ingratiating itself with a spectator. At their best, these paintings slyly took the piss off the patriarchal forces of the Ab-Ex revolution and created, in place of the self-dramatizing agon of the painter’s struggle to make a picture, a pre-made picture that released the spectator of responsibility for peering into the soul of the way-gone artist. And, as she lets her paint flow, and fly, and run down the canvas, the artist herself is released from the obligation to fully orchestrate the surface of her paintings and seems, in fact to disappear from the picture altogether. “The paint makes its own image,” as Steir says in an interview for Apollo Magazine (see link below). Elsewhere, she has said, These are pictures that paint themselves.

The advent of this series allowed Steir, who until this point had been painting under the influences of conceptual art, minimalism, Jung, and various philosophical strategies of representation, to consolidate an artistic identity for herself that showed her to be the creative familiar of her friends John Cage and Agnes Martin, and the descendent of both Jackson Pollack and the Chinese Yipin ink-splashing artists of the 8th and 9th centuries.

Steir, Cage and the role of chance

The Barnes’ press materials and Steir’s own utterances encourage us in the direction of thinking about the Waterfalls as the result of Cagean chance operations. But, as Marcel Duchamp said, “Your chance is not the same as my chance,” and it would be a mistake to write this work off as mere (or impersonal) accidents. In fact, Steir’s work is not very random at all—her technique is consistently exercised with a careful passion, a soulful precision, and a strategic elegance. And the resulting series, although radically and beautifully open to the gentle collaboration of forces just beyond her control, is both a deeply personal meditation and the creative triumph of a major artist.

Steir knows her materials exquisitely well and she deploys them variously as both a master and as a naïf. The result is that sometimes your breath is taken away by the way she’s able to work her dribbles and pours into the texture of the canvas to conjure texture as sophisticated as snakeskin…and then you glance up a foot and smile with human recognition: yeah. That’s the pucker-skinned way that housepaint dries when it spills. Although the artist and her critics want to claim that her techniques, which do not lean much on the directly controlled application of paint with brushes, are “chance operations” and that her paintings “paint themselves,” this is true more in a conceptual than a literal sense. It is also true that the archer, once she takes aim, lets her arrow fly—but it would be a mistake to call the resulting bulls-eye an accident.

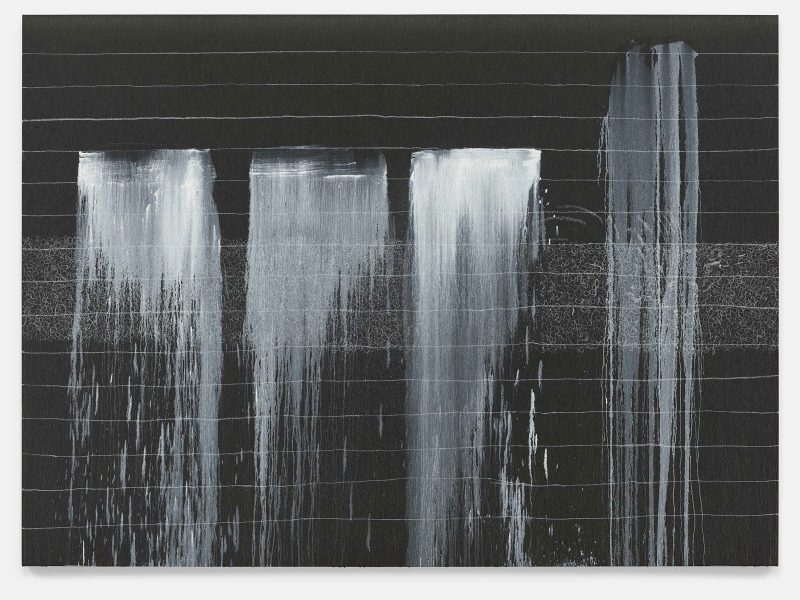

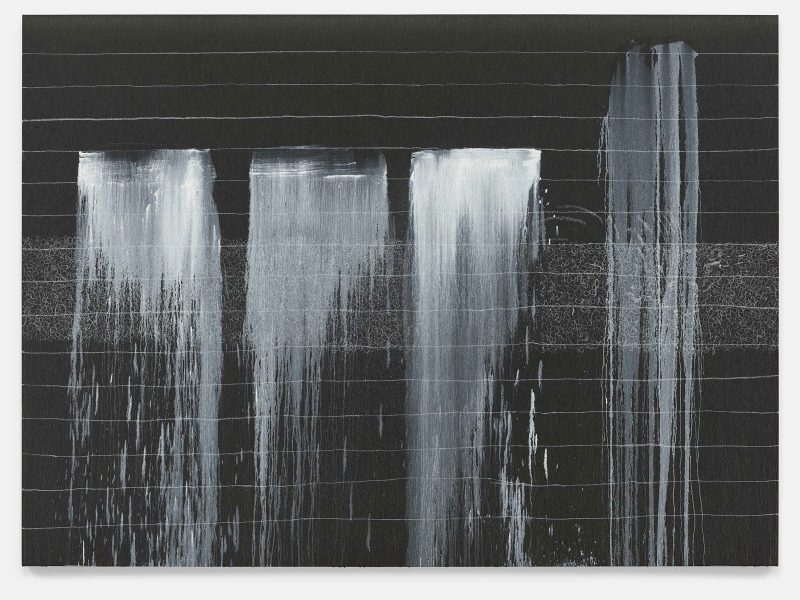

Splash, drip, whoosh – paint, water and more than waterfalls

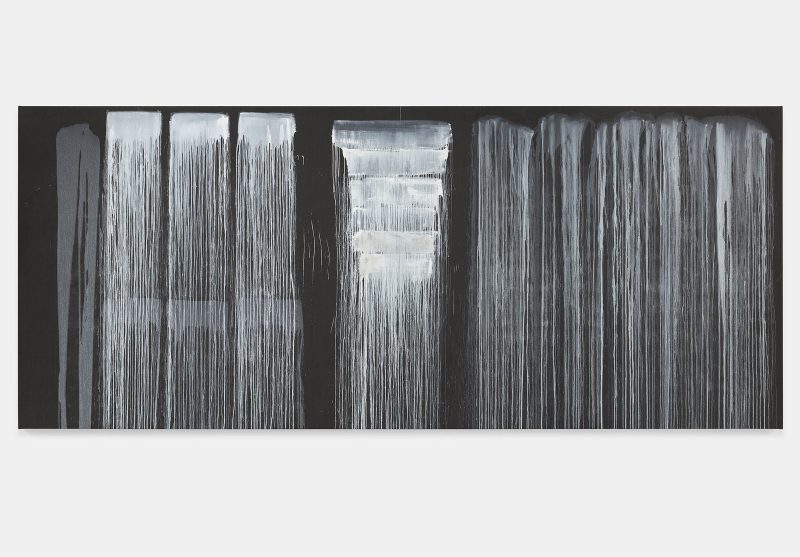

The series consists of eleven canvases, each seven feet high and ranging greatly in width—from maybe 5 feet to 17 or so. They are all hung at the same high height, in two clusters of the vast lobby of the Barnes (which is, alas, polluted with pop music, shattering the quiet of these “silent” waterfalls). On first view, Steir’s palette seems severely limited to white on black. Nothing at the Barnes says so, but in promotional materials, the individual works are titled I-XI. The light, almost entirely from windows and skylights, varies wildly, sometimes casting distracting shadows.

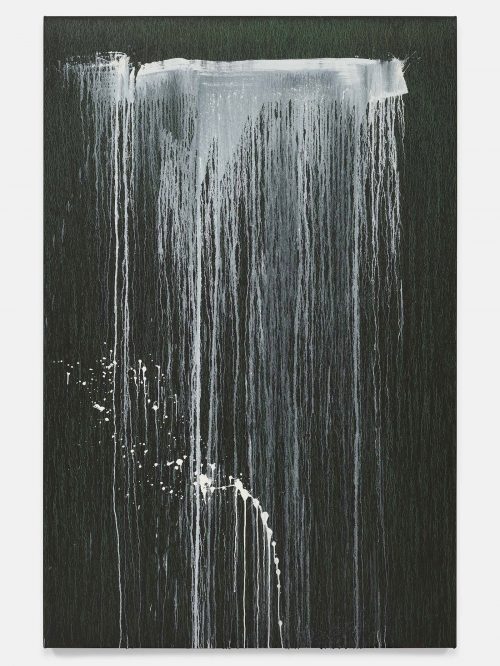

Pat Steir’s Waterfall paintings seem to be of waterfalls, of course. But they also, more profoundly, are waterfalls, or at least they begin their lives that way. Through a decidedly low-tech arrangement of ladders, buckets, bristles, and spritz-bottles, Steir flicks, strokes, pours, brushes and squirts liquid onto her canvases. The images left behind are the dried up remainders of that energy, pigment that adheres once the fluid in which it was suspended has washed or dried away. They are the results, on the one hand, of the unplannable interactions of tool, air, canvas, and gesture; the flowing, forking, and falling of the liquid and the sedimental settling out of the pigments, touching down and clasping to the ground according to laws as complex and unknowable as those governing our own trajectories. But, on the other hand, they are the result of Steir’s deliberate (and masterful) technique, evidenced here in manifold sophistications. But here are two.

First, there are the colors. While at first glance, it’s all a kind of colors of the chalkboard palette, in fact there are a rich range of blacks deployed in a variety of finishes and the whites range from sharp white to cream, and into yellow and a thinned-milk blue. Some pours deliberately shroud or echo others, and occasionally texture is created by drawing covered over by subsequent pours. Moreover, in a few canvases, Steir takes a page from Ad Reinhardt, creating varieties of black using an emerald green, almost unnoticeably but plainly, to create texture and in X, in which it is most fully utilized, a kind of glow.

Second, there is a kind of gentle progression of theme and technique in the series. The early canvases, installed by the café, make tantalizing references to the promised waterfall imagery, flirting with the illusion of dimensional space and featuring spectacular splash zones of spattered and flung paint that channel the notion of resounding rocks below and allow us to imagine ourselves adrift in swirling eddies beneath her high-hung images. But, after the wondrous pour-less explosion of V, Steir’s mood drifts inward. Paint tends to be thinner, and gradually the imagery of the falls sinks more and more into the canvases and less paint sits on them. Pours overlap less and there’s more black ground between them. The concluding canvases are like schematic echoes of dreams of waterfalls. The final canvases are so thickly layered that their bottom edges hang like stalactites. XI, hung hard against a window, finishes the series with a simple, desperate ode to the act of painting and mark-making, testimony not so much to the moment of creation, but to the revelations of what remains. The cragged lines drawn here are splayed across the canvas like school exercises, slicing through four pallid pours. A Haring-ish cartoon of a purposive splash reaches up out of the band of chalky doodling, weaving its way across the center of the canvas, almost hidden behind Steir’s last thin pour. After this, Steir delivers our gaze to the window of the gallery, with its view to the south, towards the melting icecaps, through the punishing slant light of the winter in our quick-darkening sky.

Sidebar

Does the Barnes have a WOMAN PROBLEM? You would think that the institution that effected the simultaneous eyebrow arching of every critic in America by tagging Berthe Morrisot with the sobriquet “Woman Impressionist” in its last show would find a way to avoid putting Pat Steir—in the press release for this one—into the box of “One of the few women to come to prominence in the 1970s New York art world.” This claim, which is attributed to Thom Collins, executive director and president of the Barnes Foundation and the curator of the exhibit, throws sloppy shade on the many terrific women whose work was a part of the 70s scene in New York and it pigeon-holes Steir unnecessarily. But most of all, it makes it seem as if the Barnes is out of touch with contemporary art … and the modern world.

Pat Steir’s “Silent Secret Waterfalls: The Barnes Series,” The Barnes Foundation, 2025 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, through November 17, 2019.

End Notes

Agon – struggle or conflict, from the Greek. More at Wikipedia

Agnes Martin – See Mark Lord’s 2018 Artblog piece on Martin.

More about Pat Steir

- Wikipedia

- The Apollo interview

- Painters Table video interview

- Trailer for a forthcoming film about Pat Steir

More Photos