Author’s Preface

New York’s iconic Chelsea Hotel has served as a refuge for creatives and those seeking a taste of an alternative lifestyle since the late 1800s. Initially designed as an apartment cooperative built on Socialist Charles Fourier’s ideologies of Utopia, the structure was retrofitted as a hotel with apartments in 1905. With an affordable range of units and a soundproof structure, the Chelsea became a popular stay among live-work artists, musicians, writers, transients, sex workers, stockbrokers, and dentists alike. Over the years, the hotel has gained an infamous reputation as a place rampant with rats, drugs, suicides, and murder. Despite its haunted past, it has become a sanctuary where ideas and inspiration are exchanged, art is born, and a diverse community of travelers and renowned residents coexist. Or at least that was the bohemian allure of the Chelsea- until recently.

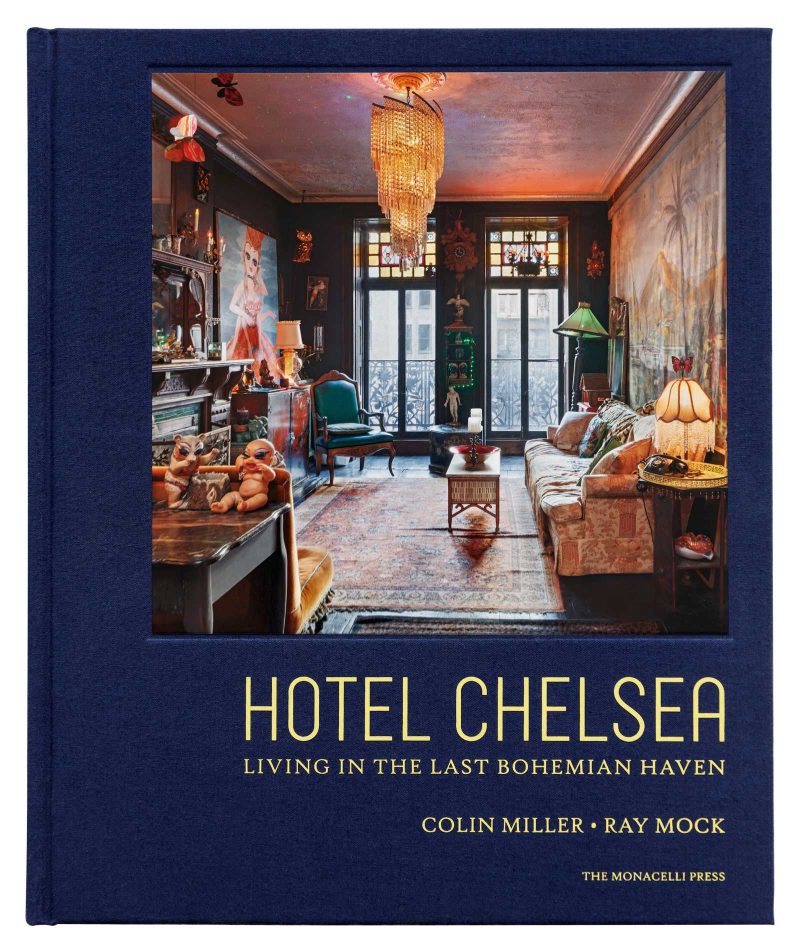

In Hotel Chelsea: Living in the Last Bohemian Haven, writer Ray Mock and photographer Colin Miller capture the hotel’s current tumultuous state amid ongoing renovations initiated in 2011 by new ownership (which has changed multiple times since). The hefty 256-page book reads like a collection of narrated resident diaries, where intimate biographical accounts and vivid memories are exposed. More than just a coffee table book, Mock and Miller’s project is a historical documentation of 19 remaining residents’* stance on the legendary hotel’s transformation and their struggle with the omnipresent threat of eviction. Initiated in 2015 and spanning four years, Mock and Miller’s project is an ongoing story of resistance, conformance, and change which leaves us to question whether the Chelsea will become just another generic and profit-driven real estate flip.

A majority of the book’s real estate is dedicated to Miller’s full-bleed unabashed photographs, complementing each resident’s story with a preview of their living quarters, a mix of original and renovated units, in all the kitsch, clutter, and glory. The pages of curated interiors read like an I Spy book, leaving the reader anticipating what eccentricity lurks behind the next door – adorned life-sized mannequins, maximalist mirrored ceilings, vintage wallpaper collections, and altars of bric-à-brac.

While the Chelsea is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and designated as a New York City landmark (exterior only), the book acknowledges the hurdles of designating and preserving interiors that have fluctuated over the past century. Judging by the stark contrast between photos of original units with stained-glass windows, ornate woodwork, and patinated plaster walls and those recently renovated with fresh paint jobs, crisp lines, and pristine flooring, there’s no denying the renovations have begun to eradicate much of the Chelsea’s historic integrity, room by room.

While some residents, like paralegal and Cher fanatic Mickie Esemplare, have accepted the renovation through enticing upgrades such as a private bathroom or larger space, others like cinematographer Tony Notaberardino are fighting renovations to their apartment in an effort to preserve the hotel’s history, claiming “people want to come here and touch the wall that Jack Kerouac touched, they want that authenticity.” Miller captures Notaberardino in his “sanctuary” of cheerful circus patterned walls painted by previous tenant and Australian artist Vali Myers. Among other original works of art featured on the walls of the Chelsea are Manhattan artist Joey Horatio’s dominatrix murals in the hallway of NY Nightlife icon Susanne Bartsch’s apartment and an India-inspired palette of decoupage by multi-disciplinary artist Gerald DeCock.

“I don’t know if it’s the hotel that changes the artist, or the artist that changes the hotel” – resident and artist Sheila Berger

It’s hard to pin down just one attribute that gave the Chelsea its elusive charm. From communal candlelight dinners in the 9th-floor hallway to informal art galleries in the lobby (featuring work often collected in exchange for rent) to staged dance performances by choreographer Merle Lister Levine in the atrium staircase, the Chelsea’s collective floor plan fostered a sense of community. Despite the solid brick structure, malleable interior layouts provided a one-size-fits-all approach, allowing residents like model Man-Lai to take over adjacent rooms after giving birth to twins or artist Arthur Weinstein to stretch out his canvasses in the halls or a vacant room. It was a place where residents could evolve personally and in practice.

Though the resident’s stories vary, they all allude to the familial community forged from a shared love of the arts and the bohemian lifestyle that ensued. The foreword, a nostalgic dialogue between sisters Gaby Hoffmann and Alex Auder, provides insight into what it was like to grow up in the scandalous playground that was the Chelsea – spitting candy into the stairwell “abyss” and hanging out on the 23rd Street stoop with “drunks, bums, and OTB addicts.” Vintage wallpaper aficionado Suzanne Lipschutz reminisces of neighbor Rene Ricard reading bedtime stories to her grandchildren every night. I imagine it’s impossible to ever feel alone in a place like the Chelsea.

Although I had known of Leonard Cohen’s hit Chelsea Hotel No. 2 and Andy Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, I was surprised to read about the countless collaborations that occurred behind closed doors, including the administration of Hanuman Books by editor Robert Foye and painter Francesco Clemente, the screenplay for 2001: A Space Odyssey by writer Arthur C. Clarke and director Stanley Kubrick, and Playboy photoshoots with model Man-Lai on her wrought-iron balcony where she and her children grew vegetables.

“After Master Manole falls to his death from the roof of the monastery he built, a beautiful well springs up in the spot where he perished. Perhaps one day the Hotel Chelsea will again become a well of inspiration and freedom for its residents, or perhaps new sanctuaries for artists will spring up in other parts of the city instead.” – Ray Mock

The Hotel Chelsea: Living in the Last Bohemian Haven leaves us with a sobering account of what it’s like to live in and love the Chelsea Hotel. As of today, residents are still battling with lingering construction and lawsuits. Despite additional constraints caused by the pandemic, residents seem to be making the most of their lives in lockdown, Chelsea style, with seances summoning Sid Vicious, dress-up reenactments of hotel legends, and Zoom discos*. It seems the magic of the Chelsea continues to prevail, despite the odds.

Hotel Chelsea: Living in the Last Bohemian Haven by Colin Miller and Ray Mock

256 pages, 9-1/2 x 11-1/2 inches, hardcover, $50

Monacelli Press, New York

November 2019

Also available on Amazon

ISBN 9781580935258

NOTES AND MORE PHOTOS

* Approximately 60-70 total residents remain at the time of publication (11/2019) of the Chelsea’s 250 +/- rooms (wall layouts have fluctuated over time)