Author’s Preface: “Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend” is on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC extended through June 27, 2021. An interview with Kathryn Wat, Deputy Director for Art, Programs and Public Engagement/Chief Curator at the National Museum of Women in Arts can be viewed here. See also the artist’s website. Clark is represented by Goya Contemporary in Baltimore. An accompanying catalog provides several inciteful essays.

A survey of Sonya Clark’s thus far 25-year career fills numerous galleries with multidisciplinary works that address issues of race, exploring Blackness and visibility. There are times when an exhibition can change viewers’ lives, and this is one of them. Through careful investigation, Clark deconstructs accepted ideas and icons in order to reveal the flaws in many of our assumptions and even in what we think we know as factual. She is an artist well-known for her medium, textiles, but the power in her works emanates as much from the stories she tells. Her definition of fiber is broad and inclusive and connects to the concept of materiality. History informs Clark’s practice: hidden history, ignored history, and altered history. For instance, we learn about the flag of truce that the Confederate troops used to surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, VA on April 9, 1865. It was an ordinary dish towel. Clark produced a replica (The Smithsonian Museum owns a section of the original), “Monumental Cloth (sutured),” (2017), by weaving two separate linen pieces and sewing them together with silk thread.

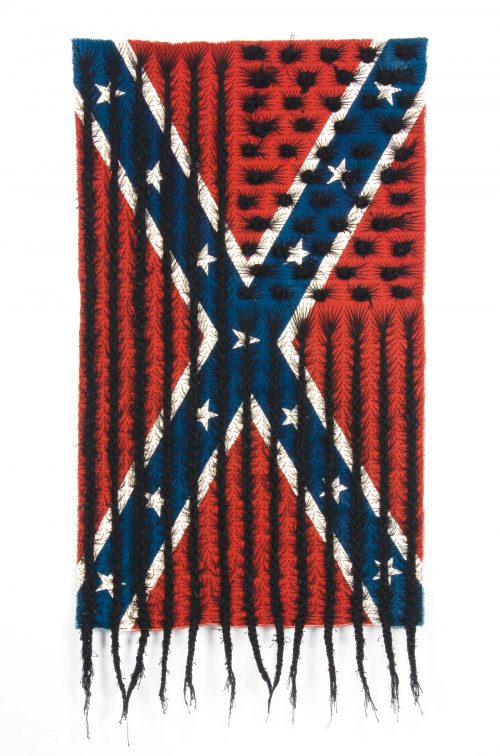

We see in this quiet work the symbolism of a wounded country stitched back together after the Civil War. Clark utilizes the intensive labor of weaving to suggest the complex and difficult work of reuniting the country. That flag is in many ways a truer accounting of the terrible loss of life and end of the South’s secession from the Union. It contrasts dramatically with the more popular and well-known rebel flag that represents a hurtful reminder of slavery and Jim Crow and has been the object of much conflict in recent years. Included too are several works where she unraveled commercially purchased Confederate flags.

Many flag works are on view together in one gallery. In addition to the historical context of each, the presentation of them side-by-side, along with their aesthetic elegance, engages viewers. They demonstrate not only Clark’s craftsmanship but also her research. An extremely thoughtful artist, she connects the past to the present, and the museum’s labels provide excellent information. “Black Hair Flag” (2010) is comprised of thread applied to painted canvas using hairdressing techniques in stitched Bantu knots and cornrows. They form a design that emphasizes the stars and stripes of the U.S flag and the X of the Confederate Battle Flag of the Army of Northern Virginia. We learn that in 2010, the Virginia Governor declared April Confederate History Month without referencing the fact that the wealth of that state (and indeed of the nation) was built on the labor of enslaved people; that omission was the cause of much controversy. Clark comments that “The purpose here is to discern and dismantle the complexity of the symbol, the history, and the hatred, and to work—or unwork—it together.”*

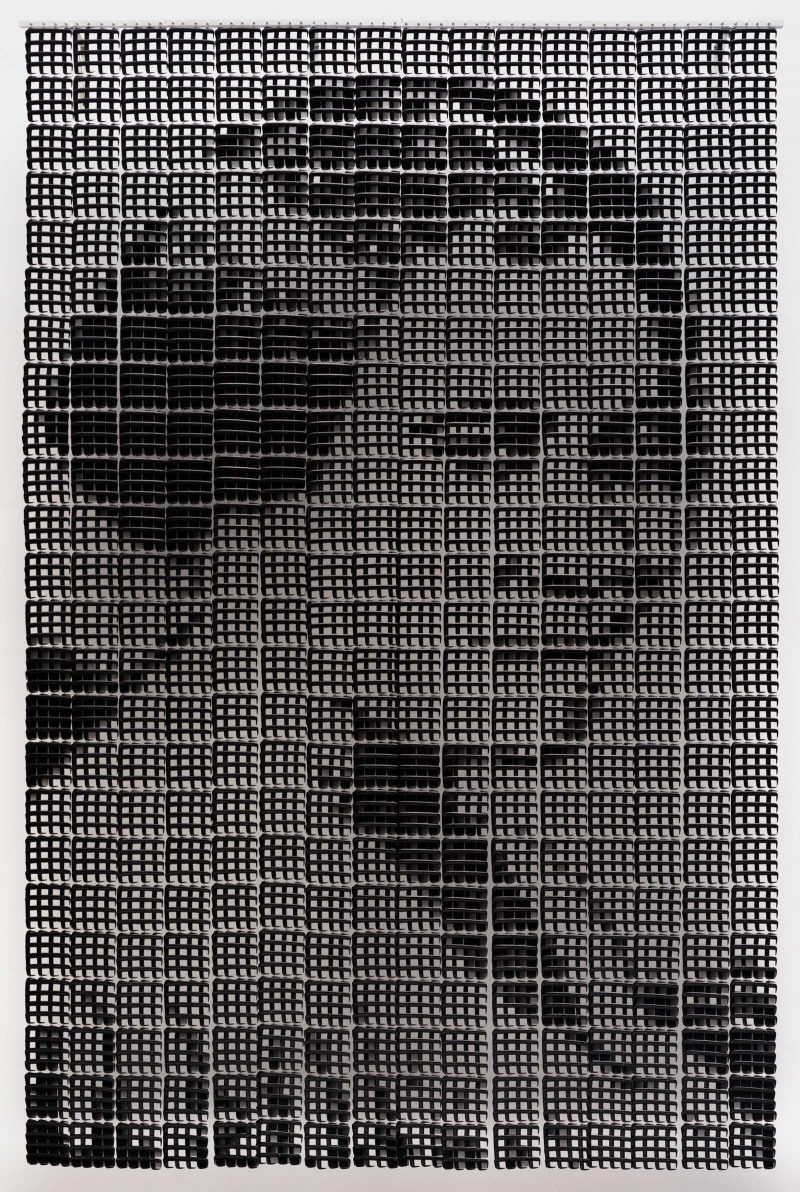

The theme of hair inspires the artist. Throughout the exhibition we sense that Clark proposes a more positive life view; that we can choose our symbols and the people we admire. One of her most important works is a very large image of Madam C. J. Walker constructed of black plastic combs, (2008). While I have seen this piece in exhibition twice before, it never loses its impact. Madam Walker was the first Black woman millionaire, and she made her fortune from hair products for Black women. Clark states that the combs are made in the United States and stamped “unbreakable,” representing the white man’s world. She uses them to refer to Madam C. J. Walker who “walked in a white man’s world and claimed her space.”** She appears again several times in the show, with one image being a detail of a larger installation of portraits made of thread and combs, “Hair Craft Tapestries” (2014). This intimate image contrasts with the earlier large portrait of Madam Walker and is installed perpendicular to it.

A much smaller, no less powerful comment on hair is “Mom’s Wisdom or Cotton Candy,” (2011), made from the artist’s mother’s white hair. Here, Clark draws upon knowledge about her Yoruba lineage where white hair is associated with wisdom. “Cotton with Hair” and “Flag with Hair,” both (2017), ethereal works where hair is pulled through Khadi paper, suggest sewing and hair styling techniques. Hair DNA contains information that tells the story of our heritage. Clark learned sewing techniques from her grandmother and worked with hairdressers on a large project, “Hair Craft Project Hairstyles” in 2014. She adapts these techniques to examine history and provide a less known narrative. She says, “My charge here is an amplification. It’s not like I found something that no one had discovered before. It’s just that it hadn’t been talked about.”***

In “Rooted and Uprooted” (2011) Clark twists and braids black cotton threads into plaits. Her mother was Jamaican and her father from Trinidad. Much of her work addresses the African Diaspora and the Triangle Trade where sugar was a cash crop that required extensive labor. Clark can trace her European roots back to Scotland, while it is more difficult to know about her family’s African origins. This work symbolizes that status in that the rooted section of the sculpture on the left pulls tight, while the unrooted half suggests the loose ends of not knowing her African ancestry.

“Twisted Diaspora” is another work of the same year that addresses the topic by installing cotton thread twists onto a primed white canvas in a Mercator-projection map. This type of map was created in the 16th century for navigation. It is a flattened cylindrical view of the world that depicts north as up and south as down while including local directions and shapes. The irony here is that it was exactly this type of map that would have been used to navigate the ships of the Triangle Trade. In Clark’s interpretation, there are more twists over Africa with others dispersed to ever increasingly distant geographic locations, symbolizing the Diaspora.

A more recent work that examines how our collected experiences can involve casual and unconsidered references to race is the neon “Schiavo/Ciao” (2019). Made up of lighted text, it toggles between the two words, and demonstrates Clark’s exploration of media and her fascination with language and meaning. We learn from the artist that the word ciao comes from the word schiavo, which literally means slave. We say ciao to mean “at your service,” but its root is the word “slave.” Here, Clark builds upon the work of artist Glenn Ligon who utilizes language, both in paint and neon to examine the dualities of racism (“Double America”). Clark has used text in her works before, but this is her foray into neon sculpture. And the context of her piece is the broader universal lesson of how racism permeates our culture in many unrecognized ways.

Throughout her 25 years, Clark has created on two interconnected levels— the contextual and the visual. The beauty of the hand-crafted techniques presents and supports the narrative. She is an artist and historian, storyteller and maker. When a guard engaged with me while I was in the galleries taking pictures for this article, he wanted to make sure I told the artist that many people visited the show and that it was an important exhibition. I cannot agree more.

“Sonya Clark: Tatter, Bristle, and Mend” on view at the National Museum of Women in the Arts, Washington, DC extended through June 27, 2021.

*Sonya Clark, statement in “Sonya Clark, Tatter, Bristle, and Mend,” exhibition catalog, (Washington DC: the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2021), 115.

**Sonya Clark, statement in “Sonya Clark, Tatter, Bristle, and Mend,” exhibition catalog, (Washington DC: the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2021), 136.

***Sonya Clark, statement in “Sonya Clark, Tatter, Bristle, and Mend,” exhibition catalog, (Washington DC: the National Museum of Women in the Arts, 2021), 120.