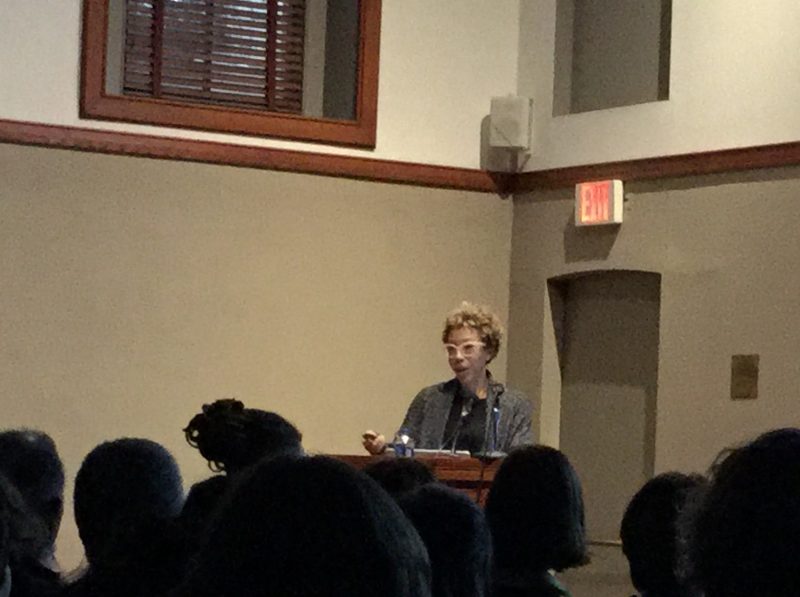

It’s 12:00 noon on Friday, March 2, 2018, and the SRO audience in the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts auditorium is told that the speaker, Amy Sherald, is delayed. The artist’s train to Philadelphia is late. No surprise. The Noreaster’ bombogenesis snow storm that nobody expected to be quite so bad is raging outside.

The audience sits chatting, a noisy burble of voices in the big, high-ceilinged room. At 12:05 PM, the artist arrives and slips to the front, greeted by the hosts who will introduce her. It takes a minute for the audience to realize she’s in the room but once the fact registers, the burble becomes a hush, and Sherald, sensing the change, turns around and says “Hi.” The audience responds in one voice, “Hi.”

The introduction mentions Sherald, painter of portraits of African Americans, including the recent and much celebrated portrait of former First Lady, Michelle Obama, had, among many other things, done a residency with the Norwegian artist, Odd Nerdrum, he of the weirdly depressing figure paintings in brooding Nordic landscapes. This information is unexpected — Nerdrum’s story-telling allegories are apocalyptic; Sherald’s color-filled portraits are life-affirming.

Painting responses- to Kara Walker and to absence of African Americans in history books

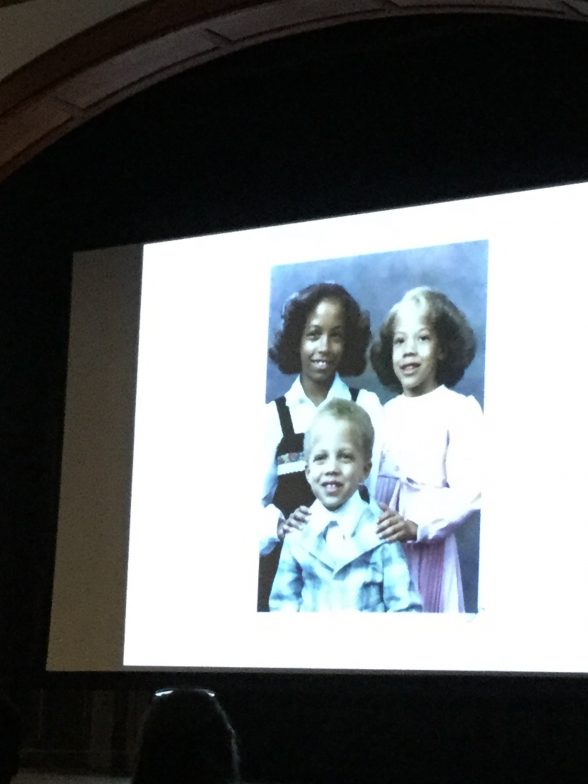

She starts the talk with a family photo of her and her two siblings when they were children. She says it was just about then she decided the world was codified and was codifying her. It was “the narrowing of my imagination.” She was not pleased with this.

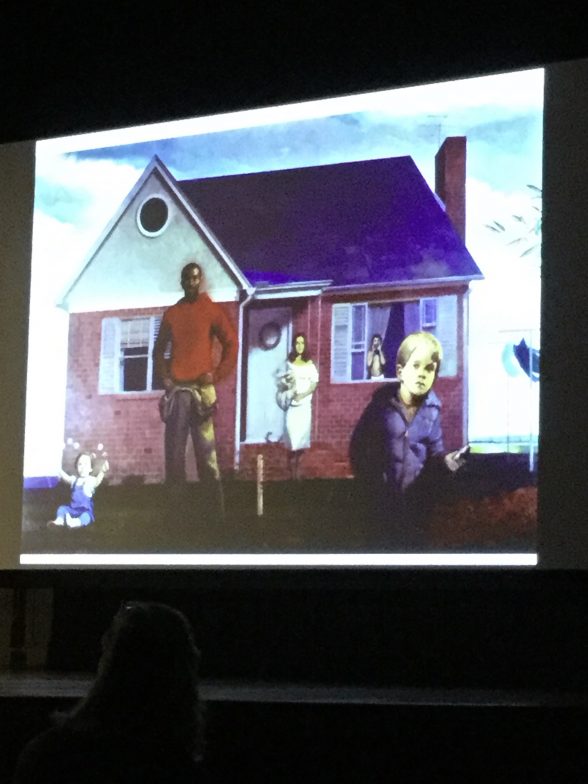

Sherald talks about many things in her hour-long slide lecture, including her residency with Nerdrum (it was formative) and about the first image that had an effect on her, a painting by Bo Bartlett, which she saw in 6th grade, and which made her know she could be an artist. (Bartlett is from her hometown, Columbus, Georgia, and works with American themes, something Sherald is committed to.)

After a three-year stint in Pre-Med in college and having trouble with biology she switched to art, but she had a lot of catch up to do. (She was still catching up in graduate school. She calls herself a self-taught artist.) It seems she was a natural portrait painter. Her initial paintings were of sci-fi alien women, very dark toned canvases with alien landscape backgrounds. After that, she went to an artist colony in Panama for a month and developed a love of color. Grey scale is an aesthetic decision, she said. Pre grey scale, she went to the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, FL, and was influenced by the colors and patterns (stripes).

After graduate school, Sherald saw Kara Walker’s scathing cut outs about the antebellum South, at the Whitney Museum in 2008 and said to herself “Now what am I supposed to do with that?” Not that she didn’t like it but how could she work? Her work is a response to Walker’s, she said.

She did research and found no African Americans pictured in history books. She found archival images of African Americans and got into portraiture through the old photos. “Old photos don’t show the pain of our experiences.”

“I consider my portraits a criticism of the art historical narrative,” she said.

It takes her a long time, four-five months, to name a painting, something she finds difficult. She partners with her sister in the naming of works. Sometimes she uses books of poetry to inspire her titles. Her titles are lyrical counterpunches to the fierceness of the people portrayed. Check Sherald’s website for examples.

She talked about her complex feelings of being American and being black and gave this example. “I was living in Norway. George Bush was president. You told people you’re Canadian.”

Q+A with audience members

How do you get your art out there?

Make sure you’re on your path not someone else’s. I used to go to openings hoping to meet someone and get a break. Then realized NO. I should be in the studio working. I developed a relationship with collectors, and one made an introduction to a gallery.

Question about the Michelle Obama portrait..How do you push back against public perception and get out there what you want to convey?

I had to treat it as any other painting. It’s about composition, the pose, the dress. They live in the same space; they tell the same stories (as her other works). Commissions are not my thing but Michelle has je ne sais quoi…she has a universality. They asked me to do it. I agreed to do it and I painted it.

Question about taking four years off without painting…

I had to be home, had to take care of my family. Things happen to you when you’re quiet; lived experience gets put in the art. I was 33, (in) Georgia. If I hadn’t had those experiences I wouldn’t be here. Four years and no painting, but I remembered, and when I painted it was there.

Question about painting…

Paintings are the easy part. Eighty percent is research – that’s really important. Paintings are like a journal…they’re what I needed to get out. I never felt it was a challenge.

Question about her reaction to Kara Walker’s work…

This work is a visceral reaction to it (Walker’s work). Not that I didn’t like that work.