Dario Robleto, he of the mysterious sculptures made from ground up vinyl records and pulverized bones–from humans and dinosaurs– came to the University of the Arts to explain himself and his art work today.

His talk was part five of the UArts six-session Food for Thought summer lunchtime series.

Robleto (right), who at 31 has made marks in New York (including at this year’s Whitney Biennial), Los Angeles, and Paris, hails from San Antonio. He’s been showing pieces from his trilogy project that’s been four years in the making, and apparently he’s still hard at it.

The trilogy is nothing if not ambitious, with a back story about a fictional soldier on various American battlefields in the course of 200 years. Our hero, a Robleto stand-in, dies, is maimed, is hurt, but ultimately, in parts 2 and 3 of the trilogy, will regenerate, Robleto said. (Left, a kaleidoscope made from trinitite, the material created by an atomic explosion melting the desert–a product of war, and marbles made from clay or bullets by soldiers.)

The trilogy is nothing if not ambitious, with a back story about a fictional soldier on various American battlefields in the course of 200 years. Our hero, a Robleto stand-in, dies, is maimed, is hurt, but ultimately, in parts 2 and 3 of the trilogy, will regenerate, Robleto said. (Left, a kaleidoscope made from trinitite, the material created by an atomic explosion melting the desert–a product of war, and marbles made from clay or bullets by soldiers.)

The thing about Robleto’s sculptures is they are so layered in content, material and meaning but not all those layers are visible. “Our Sin Was in Our Hips” is a sculpture of a male and a female pelvis, the male on top. That’s what you see. What you don’t see is that the pelvises were cast using old records, the male pelvis from Robleto’s father’s 12″ rock ‘n’ roll records, the female pelvis from his mother’s old 45 rpms.

Robleto is a kind of art novelist. He imagines how people would have responded to things that really happened. So for this piece, he imagined how his parents and their generation would have learned their sexuality via rock ‘n’ roll, and “how a generation was made to feel so dirty and sinful in their musical decisions.” But it’s thanks to the inspiration of sexy rock ‘n’ roll that Robleto is alive, and he showed a charming delight with this concept.

The sculptures are Robleto’s own form of regeneration. He comes from a dj background, using music and the concept of sampling to take something that’s just gathering dust, or something that’s old, and recreating from it something new. And music is everywhere in his pieces, whether resurrected as vinyl or as sound samples or even as song titles.

The sculptures are Robleto’s own form of regeneration. He comes from a dj background, using music and the concept of sampling to take something that’s just gathering dust, or something that’s old, and recreating from it something new. And music is everywhere in his pieces, whether resurrected as vinyl or as sound samples or even as song titles.

“At War with Entropy of Nature” (back side, “Ghosts don’t always want to come back”) is a casette tape case created from bone dust from every bone in the body, he said (should I take this literally?). He created a sound track from samples of voices of the dead. (I don’t know where the fact begins and the fiction ends in his description of his materials, but clearly, here we have jumped off into his imagination.) For the samples, he imagined everyone on the same battlefield at once. “If you remove the politics of the moment, no one knows what they’re doing. They’re just shooting and fighting.” So the soundtrack is chaotic. And the tape itself comes tumbling out of the cassette in a jumble and tangle– the “voices leaving the shell of the body,” he said. (Tape shown)

If you don’t know the thoughts and the materials that went into the piece, I don’t know that you would take the trouble to understand, because in general, Robleto’s pieces are more conceptual than visual. So I found it interesting that he thought he would be slowing gallery-goers down for longer than their standard 3 minutes per art work. But the content is too deeply buried to succeed at that unless, perhaps, it was a large enough selection of things to make the pattern of thinking accessible.

The sculptures feel creepy and Victorian–bones in vitrines, mad science and snake oil.

The sculptures feel creepy and Victorian–bones in vitrines, mad science and snake oil.

The work is also ritualistic. Words incorporated in the pieces and in the descriptions of the materials are incantatory; the materials are there for their magical and curative properties; the stories, available to initiates willing to undertake a study of them, are part of a belief system for raising the dead (left, “Vatican Radio” dedicated to Pope Pius XII, the metal from melted shrapnel, bone and bullets, the audio from a soundtrack calling draft lottery numbers, a woman’s gasp manified and echoed).

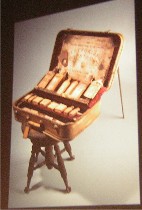

And there’s also a touch of boyish romance–a love of the old music; a love of the ’60s. Robleto uses vinyl dust from Bob Dyland and Jimi Hendrix, for example, cast with prehistoric whalebone dust in “Hippies on a Ouija Board–Everybody Has to Cling to Something” (right)

And there’s also a touch of boyish romance–a love of the old music; a love of the ’60s. Robleto uses vinyl dust from Bob Dyland and Jimi Hendrix, for example, cast with prehistoric whalebone dust in “Hippies on a Ouija Board–Everybody Has to Cling to Something” (right)

The piece is a hand-carved old-fashioned valise, stuffed with a cast Ouija board (for talking to the dead) and old-fashioned homemade nostrums in bottles carved from bone. What’s he thinking about? “Hippy problems–arthritic joints, loss of hope.” Dario, you’re such a sweetie, but please don’t write me off yet. I’m not quite ready to succumb to depression and skeletal failure.

By the way, the snake-oil salesman who owns this sample case of remedies works for Lomax and Cleaver (named after black power leader Eldridge Cleaver and music collector and archivist Alan Lomax). He’s talking about my generation. (See, we writers have our own version of sampling.)

Robleto has a lot of stories to tell of people from the past. And he’s got a lot of really rich thoughts about the meaning of life on this earth. Furthermore, I find him less obscure and more humanitarian and humanistic than that darling of nouveau cosmologies and imagined worlds, Matthew Ritchie.

I wonder how he’s going to pull of the trick of creating parts two and three of his trilogy–“Southern Bacteria” and “Diary of a Resurrectionist.” I can’t imagine how someone who makes this odd but powerful melancholy work that channels the past will somehow move his work’s affect into a more upbeat theme.

As for the secret meanings, unspoken samplings and hidden pasts embedded in the work, the more you know, the more you like the work. But only the shaman has the knowledge to decode it all.