The Prague Spring of 1968, one of the first revolutions behind the Soviet Iron Curtain, brought economic, social and political reforms to Czechoslovakia. But in the summer of that year, Russian tanks poured into Prague to halt the reforms and crush the uprising. Though Czechoslovakia remained under the thumb of the USSR until the Berlin Wall fell in 1989, the Prague Spring unleashed a cultural revolution that uplifted the Czech people, and raised the profile of writers like Václav Havel, who became the country’s first president (1992 – 2003).

50 years after the Red Army rolled through its streets, Prague is occupied by another presence altogether — dozens of monumental artworks. Men and women float above city streets with umbrellas while giant babies crawl about public parks or climb the Žižkov television tower. Massive iron chairs perch on the banks of the Vltava River while what is probably the world’s largest working outdoor metronome ticks away.

In August, my friend MJ Moon and I spent a week in the Czech Republic’s capital, wandering this jewel of a city and touring the outdoor public artworks. MJ took photos and offered some commentary.

Kafka

In addition to a museum devoted to Franz Kafka, Prague offers other monuments to one of its favorite sons. Sculptor Jaroslav Róna’s 2003 Memorial uses an image from Kafka’s story, Description of a Struggle. At the intersection of Dušní and Vězeňská streets a large, headless and handless man in bronze carries a smaller man on his shoulders. “The thing about the Kafka sculpture is that at every angle you are getting a different reflection, a different point of view,” said MJ. Kafka wanted his manuscripts burned upon his death – luckily they were not.

Jan Palach

Prague features several memorials to Jan Palach, a Czech history student whose self-immolation in protest of the Russian occupation made him a symbol of the resistance. A large portrait of Palach is painted on a building on Legerova Street, near the clinic where he died. He is joined by a portrait of Catholic priest Josef Toufar, who was tortured and killed by Communists.

Along the Alšovo Riverbank in Jan Palach Square (formerly Red Army Square), twin granite, steel and wood sculptures by American artist John Hejduk honor the young martyr. The House of the Suicide and The House of the Mother of the Suicide (1990-1991), with their 49 upward-pointing spikes, were created in Atlanta Georgia and Prague. On stone plaque at the base a poem is inscribed in English and Czech: The Funeral of Jan Palach.

Another monument to the fall of Communism appears along Narodni Street in the Old Town – a bronze relief of hands reaching out to passers-by. Entitled 17.11.89, the piece commemorates the date Czechoslovakia wrestled itself free from Soviet rule and the students beaten during Prague’s Velvet Revolution. “The hands are of protesters, aren’t they?” pondered MJ. “I don’t see a signature but someone scribbled ‘Peace is dead’ on the plaque. Ironic, isn’t it?”

Penguins & Hanging Freud

David Cerny, the Czech Republic’s most well-known sculptor, created perhaps the most hashtagged public artwork in all of Prague – Proudy – a 2004 bronze sculpture of two guys peeing at each other in a Czech Republic-shaped pool in a courtyard outside the Franz Kafka Museum. We caught his “Hanging Man (Sigmund Freud),” dangling from a pole high above the intersection of Na Perstyne and Jilska streets. Most folks never look up to see this piece, perhaps for the same reason most people never dive down into their unconscious, or pay close attention to the world around them.

What we missed were the 34 wonderful Penguins also by Cerny. These baby penguins are painted yellow, and are visible from Kampa Park marching in line above the Vltava River. The work reminds people about the imminent dangers of climate change as they are all made of recycled plastic containers.

I WAS BORN IN YOUR BED

While art seems to breathe easy in this city, and is embraced by both the government and the local merchants, many of the works are unsettling — even challenging the core of Czech identity. While browsing some vintage music shops near Prague Castle, MJ spied a text-based work printed above some café tables. I WAS BORN IN YOUR BED, by Daniel Pešta, explores how an individual’s fate is predetermined by race.

Pešta’s multi-media work, featured in the 2013 Venice Biennale, focuses on the Romani or gypsy people, an itinerant population numbering roughly four million worldwide, and a significant Czech minority. The “Roma” have struggled to find their place anywhere since their migration from India more than 1500 years ago (according to some estimates). Though the Roma are actually native to the Czech Republic they were officially labeled undesirable after World War II, and Romani women were sterilized as part of a state policy which continued right up until 1991.

Sculpture Line

The Czech Republic has embraced public sculpture so much that a walking tour was launched 2015. The tour now includes some 54 pieces in a “sculpture line” network in 14 cities, with more works slated for 2019. Of note, there’s Andrej Margoč’s giant pink Greedy Pig, a sour take on the nemesis of sugar in the form of a tongue at the entrance of Frank Gehry’s Dancing House aka, Fred and Ginger (1996) on Rašínovo nábřeží.

One of our favorites is “Like” in the cozy cobblestoned Jungmann Square. A sarcastic take on the inanity of our internet lives by young Czech artist Krystopf Hoseck, it offers the passerby an excuse to post on FaceBook or Instagram with this bony, ironic and dead thumbs-up.

“It’s funny, yet there’s something dark about it,” said MJ. “It echoes UK artist David Shrigley’s bronze ‘Really Good’ installed in London’s Trafalgar Square two years ago. But in the end, it shows the lack of attention, as if it died liking something… We walk past and it likes us! It likes everything, in fact.“

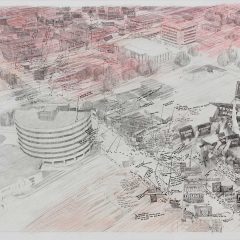

Metronome

As MJ and I are both musicians, we hoofed it up to the hill peak above Prague to see the world’s largest working metronome up-close. “It seems like a thousand steps to get to the top,” said MJ. “The metronome was built in 1991 and placed on a plinth left vacant after a statue of Stalin was destroyed in 1962 – probably by anti-communists. All art seems political in Prague – even statues that have been destroyed or removed or replaced. A metronome suggests stability, reliability – it’s political. I can imagine the days when Stalin was there surveying all of Prague. Now there’s a metronome…at least it’s not a tank!”