Full Disclosure! James Dillenbeck is one of my favorite comic book artists. His work explodes off the page in a kaleidoscopic storm, hitting your subconscious like an apocalyptic dream in vivid color. It’s the kind of dream that feels wild, dizzying, hypnotic and utterly dangerous and yet impossible to want to wake from. Dillenbeck is the artist of a comic book I’ve written and created called Black Vans, a series of four comics that tell the story of queer POC hackers Bo, Allie and Snacks who help super-heroes with intel, communications and tech support. Their story takes a wild turn when super-heroes start disappearing on their watch and now the hackers, the EQs as they’re called, have to save the world.

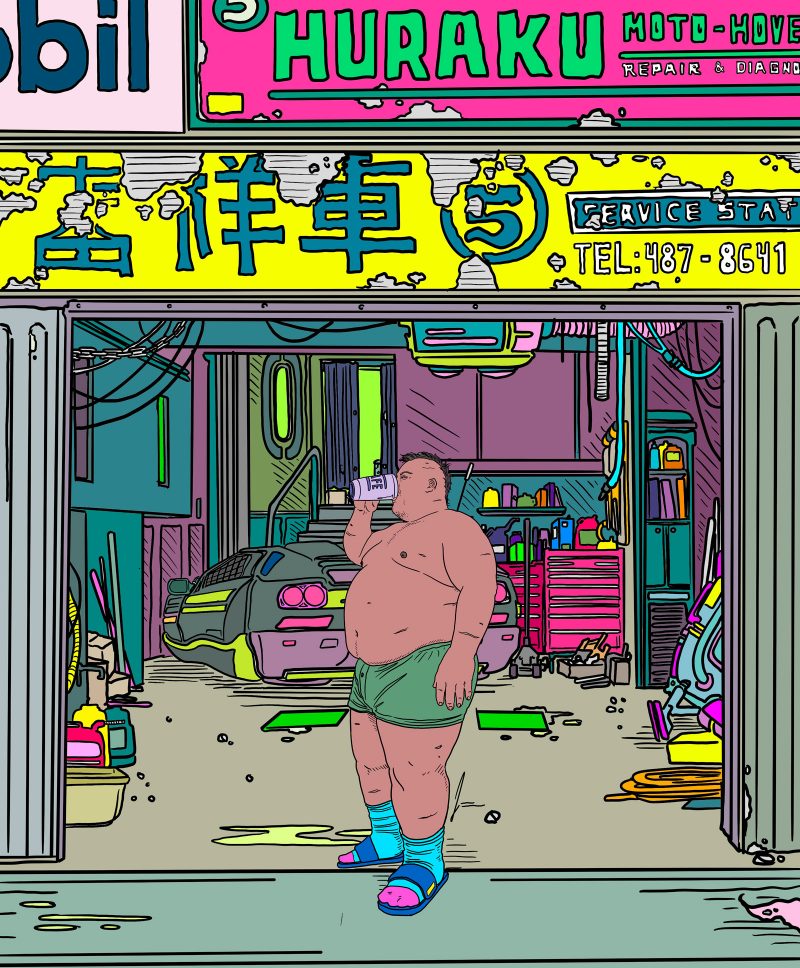

I asked Artblog if I could chat with James a bit ahead of the release of our second issue of Black Vans and in conjunction with the release of Some Strange Disturbances, a black and white mini-comic about a world-weary sumo wrestler from the imprint HSP , as well as his upcoming dystopian cyberpunk tale featuring his own original character Beefchunk. Having discovered Dillenbeck a few months before the pandemic hit, I spent so much time combing through his Instagram, staring in awe at his work– it all has a Moebius-meets-Geoff Darrow quality for its hyper-detail. It’s art that is influenced by the stylistic ephemera of sci-fi artists like Syd Mead and filmmakers like Tarsem Singh, but it’s James’ patented “cartoon realism”, helped tremendously by his bold, immersive colors, that makes Dillenbeck’s work stand out. That and his characters: heavy-set gay men– known colloquially as Bears– who are cyberpunks, barbarians, or cyborgs all in strange, often futuristic settings, as otherworldly as they are grounded, as violent as they are incredibly, dangerously sexy.

As a person who was at one point fat, James has kept the torch going for body-positive, fat inclusive art in such a powerful way. We talked about desirability and the responsibility of creating body-positive, truly diverse work in a comics world that often wants to shun those ideas. Let’s meet James Dillenbeck!

[ED. Note: Check out Alex Smith and James Dillenbeck’s Kickstarter for “Black Vans #2” before the campaign ends on Sunday, August 21 2022, at 10:38 PM!]

Alex Smith: What is the elevator pitch for James Dillenbeck’s art?

James Dillenbeck: Oh man… I guess I just find that [when] talking at these conventions and fairs I find myself saying the same thing. Like, I love science fiction and cult-y punk shit, but I really love the idea of putting the men I find beautiful into lead roles– like, I love Frank Frazetta, but I thought, “what if this was actually a hot guy and not just some basic himbo?” (LAUGHS) But basically, I guess the pitch would be taking these [larger] men and making them cult heroes, if that makes sense?

AS: No, it does. What was it like finding your voice as an artist– not necessarily when you first picked up the pen, but can you describe how you kind of evolved into this?

JD: I think– and I bring it up because I think it relates– I would do a lot of self advertising, DIY stuff for bands I played in. Before that, I would just create mini comics on the side of notebooks at school and draw some hidden, more queer stuff in the back of those notebooks. I think after I started getting fed up with some of the jock behavior in band circles, I started enjoying the privacy of recording stuff by myself, drawing stuff by myself; then I would have these two friends who wanted to get into making a comic, so that was the first time I put my foot on the gas with trying to create characters and designs. After that, one of those two people passed away and the project just kind of evaporated, but because of that book [we were about to create] I started drawing a lot. In that book, I kinda shoe-horned in fat characters– we’d get an idea for a character and I’d make that guy fat.

AS: Did your friends have a problem with that or–

JD: I think it was more like, “Oh…okay.” I was a newly out person in my early 20’s, so I think with that project I felt like I was doing a lot of pushing, but it also got me into character design, world building on a real scale and not just messing around in my notebook. From there, I think I was pretty sour on art after my friend passed away, but I started to feel like creating art was a cool way to create with him in mind. He was always the biggest support system at school for all my art. He’s the kinda dude who was– when I was wearing skinny jeans he’d be like, “yeah man!” He’s the kind of guy who would show up at like, Westboro Baptist Church protest and get physical, he was just a bad motherfucker– he wasn’t meant for this world for those reasons but he was awesome. So art became my easiest way to connect to his loss. He was also the first person to tell me that my naked big dudes were awesome, so that was the first encouragement I ever got from anybody that didn’t feel double-edged or accusatory. He found them and was like, “Dude, why are you hiding these? These are the best drawings in your notebook!”

AS: Do you think those were your best drawings because they came from a more emotional place?

JD: Yeah. And he could just tell because I was spending more time on these and he was really good at seeing this kind of stuff. He was like, “this is the stuff you really care about,” and I think meditating on his loss for all those reasons I just kinda got pushed into being like, “I’m gonna take all this cool shit I do for these other stories, I’m going to put that gear on these guys and make art that’s undeniable.” Any [social] scene has this fatphobic bullshit, but you can’t attack something when it’s undeniable. That’s the goal I think.

AS: That’s a total flex, when you’re like an artist and can create this avenue, make the shit dope as hell where it’s just something that can’t be ignored and it has this crossover appeal. Like you look at a lot of bear art, and it’s very bear community-centric and very “GAY”, but with your art it’s just dudes with messy rooms and punk rock detritus all over the place, a mechanic surrounded by the tools of his trade– I always thought that was a very interesting spin you put on it. Also, you kind of invite your characters into sci-fi realms that are generally dominated by hyper-muscular and thin bodies. You’re putting fat characters into these roles but none of the qualities are diminished, none of the aspects that people find interesting about cyberpunk and sci-fi are being diminished at all.

JD: Yeah, that’s something I’ve always loved– the idea of creating a character’s vibe, right down to their bedroom, is so fun. I want my cyberpunk shit to be as cool as any other; I look at a lot of other stuff and I just know [they’re] doing the same shit that’s been done since Aeon Flux, which is fine, but at the same time there’s so much more room. If you’re still in the same lane as 1950’s sci-fi and you’re not trying to incorporate anything new in terms of the humans or the types of aliens, whatever types of things you’re drawing, you’re not really evolving. I like to see things through [an individual’s] personal lens. Like I’ve seen twink art that I still find fascinating [because] — “There’s quirks to this, you [the artist] like this specific thing about people and it shows through your work.”

AS: Do you think that queer art is sort of limiting or marginalizing to gay male figures? Do you think gay male artists that do figure work are beholden to certain types of bodies, not necessarily because they’re attracted to them but because they feel like this is the standard?

JD: I think societally there’s a really weird thing– they’ll either draw what the status quo is and accept it and enjoy it, denying parts of themselves, people they might like; or, they’re clout chasing. The limitations are only there because I think a lot of people just want to be known as good and talented rather than create exactly what they think about.

There’s a lot of artifice with queer representation, I feel like the limitations are pushed forward by this lack of honesty– I know that sounds so pretentious, but you can see it! Bear art is a great example of this where they’re so stuck in this binary, like even their fat guys are just skinny guys with a gut. Just commit!

Like, I hate drawing small characters, it’s taxing for me. But it doesn’t mean I do shitty work on them. I try to make them as important as my other characters, but I don’t think it’s the same when we go the other way. “Oh he’s big, he takes up more space, he’s got a big stupid outfit on”. I think a lot of the limitations are there because of the problems with queer culture to begin with– the racism, the fatphobia, all the shit that comes with it is projected into queer art. Sometimes, I try to moderate how much pure NSFW stuff I create because I don’t want it to just appear like I’m just hyper-sexualizing the men I like– I want it to seem like they also have depth, that they’re doing a variety of things and not that I’m just drawing them for Daddybear Tidal Wave fliers.

AS: It’s interesting what you get your most likes on, you’ll have like a NSFW post that will have 1,000 likes, but you’ll also do a post of a punk rock dude bashing klansmen or just hanging out and those posts will get drastically fewer likes. And you know, it’s not that we’d want to censor; a lot of people that are moving towards your art are looking for a chance to celebrate who they are and experience a sort of sexuality. I do think it’s interesting what people are apt to find appealing about figure work.

JD: Yeah, it blows my mind. I’ll draw something so simple like a dude sitting in a chair being contemplative, watching TV or eating noodles or something, and it’s like those are the posts where I’m like, “Yeah! This is gonna light up the night baby!” and it doesn’t! (LAUGHS) I know the people that are seeing them are getting the message, but sometimes it hurts– it doesn’t hurt my ego, but sometimes it hurts my idea of how people think about themselves or how queer culture should be.

AS: How has your work been received in different spaces– comic book spaces, queer comic spaces, and bear art spaces? I ask the latter because you tend to mostly draw bears of color: Asian, brown and Black characters. I hope the people are following all these layers of reality we have to deal with as queer comics creators! (LAUGHS) We have a lot of sub-groups.

JD: And we move differently through all of them, totally true. I think the comic space is very into what I do. Like, the average weird, indie, punk person. I was tabling at a huge show, CAKE (Chicago Alt-Komics Expo)– huge show, one of the only shows where I was tabling and like, Fantagraphics was over there, it was a big deal. But all the people that came through my table, that was the most wave of positive response I’ve ever gotten, from that eclectic group. Where as, at a queer art space, you’ll have a lot of white dudes who’ll be intimidated by the work I do because it’ll be, A— people of color, and B– fat bodies. In queer spaces, you’ll have older men who’ll surprise you and then other men who aren’t aged out of a certain way of thinking who will say some of the most stupid, rude shit. I’ve had some people say my work is “scary” before. There’s so many people that have this view that big bodies or POC are going to hurt them, or there’s some kind of perversion to the work I do. In queer spaces, when you get a good reaction, it’s amazing! But on the average, it’s the same shit we get at queer bars, where there’s the same kind of venomous, toxic people that come through and have that same attitude, and they’re going to tell you everything that’s on their mind.

AS: Why do you think that, even though we are in an era where everyone knows we should be drawing more people of color, more body diversity, people still aren’t doing it. What do you think will actually change the narrative?

JD: See, this sounds corny but I think this is the reason I love working on Black Vans so much. I think it’s going to take people who are going to make this undeniably good story and these characters are going to have to be so undeniably cool, so these people who toot the trumpet but then they don’t show up and actually do shit, they’re going to have to sit with those feelings. And even if they don’t these types of works are going to cause a ripple effect in the way people start to view this shit.

You read a really awesome comic that has characters like ours– it’s just going to have to marinate with people. I think a lot of people want to do well, want to be inclusive, but maybe not wholeheartedly. And sometimes getting to a wholehearted place requires just educating yourself a little or having that shit sink in. it’ll take something like Black Vans because there is so much crap that is just pandering, that is insincere– the number of comics or movies with a plus size person at the front, inevitably they were not written to really make that person the star, they were really just trying to get eyes on it from a different demographic. It has to be pure or something that just kind of sinks in.

AS: It’s like all the M/M romance that has a plus sized, chubby character– that character is a sad sack.

JD: Yep

AS: Almost all of it! It’s like, I didn’t come here to read about how this guy has been picked on forever, I came here to read how this bold and empowered, strong-willed character finds love. He doesn’t have to be perfect– he can have some sad sack qualities, we all do– but like, I didn’t come here to read this guy’s woe is me story. That sounds messed up but–

JD: No it’s true!

AS: And I don’t wanna read books about Black characters that are just about racism or police brutality. I’m not here to just be your avatar to talk about those issues. I wanna go to outer space. I wanna fight aliens, shoot lasers, hang out with fairies!

JD: I wanna be featured, yes. I think it’s super reductive and comes across as pandering with no intention of making that character the best possible character he can be. I’m so in my feelings about it! It’s like, what the fuck are we doing? Why even include that character? If you’re using that character to talk about an issue [like weight loss] you’re not even making a real character. Body positive is having your character being able to say exactly what any other character would say.

AS: Word. And I just– I love how you draw, man. Every character is proud, sexy as hell. Like, your characters are the kind of guys I would spend two hours in a bar just looking at and never approaching. I will look at their profile on GROWLR for 10 days in a row, and never send a hi. Period.

JD: (LAUGHS): Thank you bro. That’s what I’m aiming for. That’s why I want to make comics.