Some lines divide, some are connections drawn from A to B; some find themselves pushed against or stretched, some are made to be broken. Behind a hidden doorway down a back alley in Clerkenwell, London, a small but succinct show brings together a remarkable range of meditations on one of our most integral yet subtle cognitive tools: the line. Insecure Scaffolds at Hollybush Gardens gallery brings together work from five international artists with different backgrounds, all of whom are exploring the metaphorical, psychological, and physical aspects of line.

Pink about it

Entering the gallery, the first work that I notice is so subtle that it takes a moment’s consideration to be sure that it is a work of art, rather than simply a feature of the space. A simple pink line runs up around the entrance and along the tops of the perfect white screening walls that float in front of the brickwork to make up the gallery walls. The simple alteration simultaneously comments on the walls’ artifice and the roughness of the building that it conceals. The work is titled “Eyeliner,” by Knut Henrik Henriksen, a Norwegian-born artist living and working in Berlin, whose subtle interventions interrogate telling details in the architecture of a space. He is known for his simple yet beautiful 2011 piece on the London Underground, “Full Circle,” which explores an architectural oddity well familiar to London commuters. In two sites, the artist draws attention to an incomplete circle motif that crops up all over the Underground. Henriksen simply reinstates the missing segment of the circle–to scale, and fabricated by the same company that made the original circles–and positions the new sculptural fragment on top of the flawed circle.

Similarly, at Hollybush, Henriksen’s bright pink line highlights the construction of the white cube gallery space, which suddenly hums around me in Day-Glo. Henriksen often uses bright, striking materials to highlight the structure of a space, but this time, rather than the tape or paint that he has favoured in the past, he uses a cosmetic product: a substance that we use to enhance beauty. Perhaps it is a comment on the superficial beautification of the gallery walls, a treatment to make a space that is considered unsavoury into one that is visually suitable for the accommodation of art; perhaps it is the form of the space that he’s pointing to, somewhat reminiscent of the structure of an eye, viewers entering through a single, narrow, outlined doorway to circulate in the small chamber beyond. The line is so bright as to jump out of the light and shadow of the room as a bolt of pure colour, but on closer inspection its physicality is tangible, the dusty material falling in visible, chalky traces on the floor at the base of the walls.

Inherited stories and bland travelers

© Jumana Emil Abboud, courtesy Hollybush Gardens, London.

The colour resonates elsewhere in emerging artist Jumana Emil Abboud‘s pink envelope series, a set of simple, colourful drawings standing out on the unaddressed fronts of vibrant pink envelopes. The presentation points to the casual passing of information, doodles on scrap paper and diagrams sketched on napkins, though the envelopes are particular enough for their choice to be anything but accidental. The drawings themselves are ambiguous, hinting at recognisable representations of rain and animals and other, more abstract forms, bold marks contrasting with scribbles, all clearly intentional yet naively drawn. The drawings are drawn from Palestinian folk and fairy tales, a common theme in the Jerusalem-based artist’s work; historically, the tales were a way to pass help and give advice down through generations and bloodlines, a subtle and hereditary collective memory. I can almost feel the hand of the artist in the drawings, the childish simplicity and ambiguity of the drawings hinting at the role of personal interpretation in such traditional tales.

On the floor lies the work of Meriç Algün Ringborg, a strange collection of disparate objects, arranged precisely within the strict boundary of a rectangle, including a travel book, a typewriter, and a clarinet. Entitled “Destination: Brazil” (2014), these items are a comment on the strangely specific list of items that travellers are allowed to bring across the Brazilian border without declaring them, which paint a picture of bland and dated norms of international acceptability. This collection conjures up an anachronistic picture of a smart traveller, apolitical, occupied by depressingly neutral leisure interests, a vision imagined in the dated values of the bureaucratic customs system, here contained within a rectangle that suggests the endless pieces of paper on which its demands are spelled out.

The geometric floor arrangement calls to mind Mark Manders’ self-portrait “Inhabited for a Survey (First Floor Plan from Self-Portrait as a Building)” (1986), in which he portrays himself in the form of a static, empty floor plan constructed using writing and drawing implements. Manders used the potential instruments for writing rather than any actual statements or words to avoid dictating to the viewer, but Ringborg takes dictation as the starting point to put together a collection that houses no real person at all.

Linear progressions

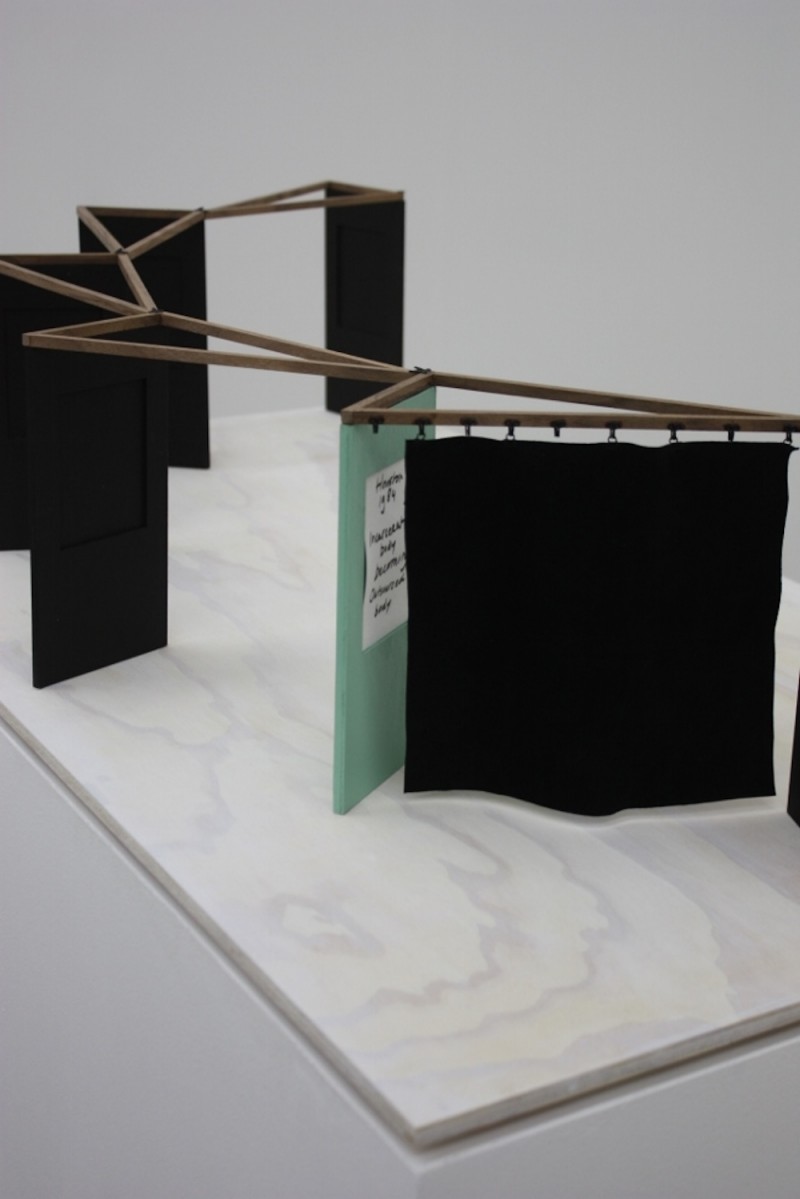

Simply presented but full of intellectual nourishment, Falke Pisano’s “The Body In Crisis” is a model, a smaller-scale representation of an ongoing body of work that she first presented in 2011. The piece explores moments in time when, as a species, our conceptual understanding of our own bodies shifted or developed. On a framed poster on the wall, the Dutch artist, who now lives and works in Berlin, identifies six historical moments that she considers to be pivotal, which can be summarised as follows:

- Pergamon, 199: death of Galen of Pergamon, who developed the theory of the four humours

- Amsterdam, Europe and the Colonies, 1571: prosecution of women deemed unproductive to capitalism, transition from feudalism to capitalism

- Paris, 1793: first university hospitals established

- Mons, 1915: first case of shell shock reported

- Paris, 1974: Lygia Clark writes on the ideological disposition of the body while in exile in Paris

- Houston, TX, 1984: first private prison opened in Houston, in which prisoners were turned into cheap labour

This idiosyncratic list seems to pick out the philosophical implications of certain revolutions in society, medicine, and politics, and the devolution of human bodies into cogs in systems that have taken control of their lives. Some writing about this research can be found on Pisano’s website, and is bursting with interesting conceptualisations. Next month, the artist is presenting a show at this gallery exploring the culture of mathematics, work that showed in Los Angeles in March; her critical eye for cultural structures will undoubtedly make for an interesting show.

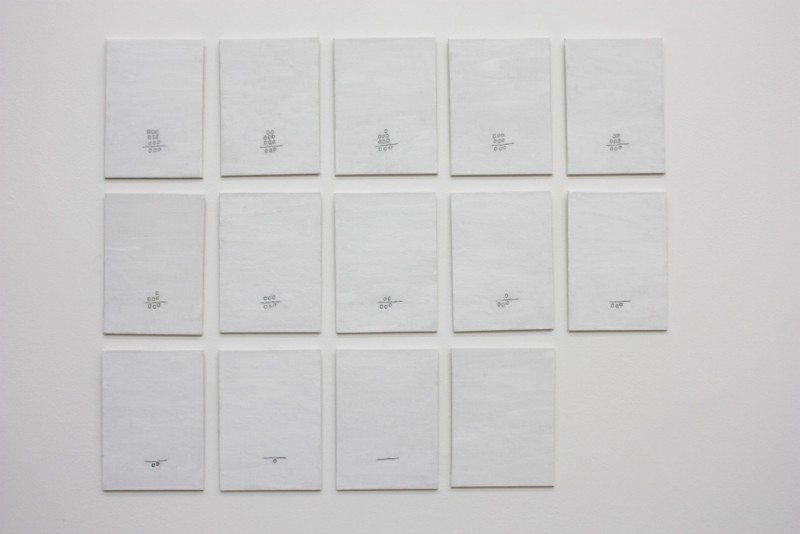

The most established artist in this show is conceptual artist Mladen Stilinović, who was prominent in the “New Art Practice” in Croatia in the late 1960s. His minimalist piece is conceptual art in the strongest tradition: a selection of circles and lines laid out on white boards on a white wall, their layout suggesting an absurd and constantly reducing set of calculations. We invented the bizarre concept of zero because it was essential for us to find a way to point at nothingness, to draw a line around what isn’t there, and this amusing piece weaves even more of a dance around it. Here, subtraction is present both in the functional mathematical sense suggested by the layout and line, and in the gradual disappearance of the zeroes, progressing toward absence. Stilinović manipulates repetition like a master. One of his most nihilistic works, “Dictionary-Pain,” simply replaces the definition of every word in the dictionary with the word “pain”.

This perfectly-balanced and illuminating show presents a remarkable range of interpretations of the theme; the line as architecture, as inheritance, as border or pivotal moment, and as notation. When a child makes a mark on paper, it is the first simple gesture, the first action through which a thought or image is made external, but embedded within that simple act is a stunning process of conceptualisation that defines and differentiates the human race. The representation of ideas through language and diagrams has allowed us not only to pass on our ideas but also to develop them, drawing and notation becoming the tools and shapers of thought. The beauty of grouping existing works together with new ones in a show like this is that it allows the pieces to work together to flesh out a concept, and the breadth of responses to such a succinct focus highlights the fertile simplicity of the theme. The range of artists involved creates a huge amount of variety, their disparate experiences unified in a satisfying exhibition.

Insecure Scaffolds is on at Hollybush Gardens, Clerkenwell, until Oct. 3, 2015.